Abwechslung ist das halbe Leben, Veränderung auch – eine hochinteressante und wichtige Neuveröffentlichung von Niccolò Jommelis Arien for Alt (und es bleibt zu diskutieren, ob Alto oder Alt) aus der Sicht eines amerikanischen Kollegen, eben Joseph Newsome, der sich meiner Meinung nach in ebenso kundiger wie kritischer Sicht über Musik und musikalische Neuheiten auslässt; er ist eine willkommene Addition zu unseren beiden operalounge-Fachleuten fürs Barocke und für Counter. G. H.

Niccolò Jommelli/ Wikipedia

Many Twenty-First-Century opera lovers, influenced by the conventional wisdom of opera in the Eighteenth Century having been dominated before 1750 by Händel and after mid-century by Mozart, would likely be surprised to hear composers active after 1740 name as an eminent innovator among their colleagues the Neapolitan master Niccolò Jommelli. Born just north of Naples in the Campania commune of Aversa in 1714, Jommelli was a prodigious boy whose musical abilities were recognized and encouraged from an early age by his well-to-do family. Considering the powerful ecclesiastical and civic patronage that he enjoyed and the espousal of his abilities by as esteemed a composer as Johann Adolf Hasse, it is strange that so little verifiable information about Jommelli’s musical education and early career has survived. Many vital details of his life—his youthful conservatory studies, his presumed tuition under the celebrated Padre Martini, his tenure at Venice’s Ospedale degli Incurabili—can only be cited with footnotes and qualifiers that document the ironic lack of documentation. Like Johann Sebastian Bach and other composers whose biographies are compromised by empty pages, however, acquaintance with Jommelli is best made through his music. In his operatic homages to two of literature’s foremost abandoned heroines, Armida and Dido, Jommelli proved himself to be a musical dramatist of the first order; an order higher, in fact, than a number of composers whose scores have been revived in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries could claim to have achieved. Jommelli deserves champions among today’s best exponents of Eighteenth-Century repertory, and in the context of this engaging new release from Pan Classics, The Jommelli Album, he finds one in Italian countertenor Filippo Mineccia. A bold artist who shares the composer’s theatrical savvy, Mineccia here does for Jommelli what Dame Janet Baker did for Bach and Händel: the performances on this disc adhere to stylistic parameters that would have been familiar to Jommelli but do so in ways that appeal powerfully to the modern listener.

The performance of Jommelli’s Sinfonia a due violine e basso that serves as an interval of sorts, dividing the sequence of arias on The Jommelli Album into two intelligently-planned halves, is indicative of the high levels of virtuosity and expressivity reached in their playing on this disc by the musicians of Spanish period-instrument ensemble Nereydas. Directed by Javier Ulises Illán, the group’s exuberant playing enlivens the spirited numbers and enhances the mood of more contemplative pieces. In their playing of the Sinfonia, the opening Largo smolders with subdued intensity that erupts excitingly in the subsequent Fuga, its subject deftly handled by both composer and musicians. The same building and release of tension shape Nereydas’s performances of the Largo and Allegro movements that constitute the Sinfonia’s second part. The strings further the progress that has been made in historically-informed performances since the early days of scrawny, strident string playing, and the continuo work by harpsichordist María González and Robert Cases and Manuel Minguillón on theorbo and guitar provides a firm foundation for both instruments and voice. Whether the inclusion of the guitar in this music is wholly faithful to the milieux in which the sampled works were first performed may be questioned, but Jommelli’s Neapolitan origins permit this element of creative license, one which detracts nothing but adds a dimension of variety to the orchestral sound. Illán supports the dramatic vignettes that Mineccia creates in each aria with tempi that are expertly judged to showcase music and singer. Wherever his music was performed in the Eighteenth Century, Jommelli is unlikely to have heard playing better than that on this disc.

1753 was a year of great importance in Jommelli’s career as a composer of opera, and that annus mirabilis is represented on The Jommelli Album by arias from a pair of his most accomplished scores. Premièred in Torino, Bajazette was Jommelli’s contribution to the musical legacy of the eponymous Ottoman sultan’s confrontation with the legendary Tamburlaine, an operatic obsession of sorts that extended from Händel’s Tamerlano and Vivaldi’s pasticcio Bajazet to Mysliveček’s Il gran Tamerlano. From Bajazette, Mineccia sings Leone’s exacting ‘Fra il mar turbato,’ a simile aria as exhilaratingly evocative of its tempestuous text as any of Vivaldi’s celebrated arias in a similar vein. Braving the divisions with absolute confidence, Mineccia makes the aria a dramatic as well as a musical tour de force. The ease with which he ascends into his upper register, which occasionally leads to over-emphatic projection of tones at the crests of phrases, is reminiscent of the pioneering singing of Russell Oberlin. Like fellow countertenors Max Emanuel Cenčić and Franco Fagioli, Mineccia possesses the ability to convincingly evince masculinity whilst singing in a high register, and his technique enables him to devote considerable attention to subtleties of text and the composer’s setting of it. Also dating from 1753, in which year it was premièred in Stuttgart, the La clemenza di Tito excerpted here was Jommelli’s first treatment of the popular libretto by Metastasio, to which he would return with revised scores for Ludwigsburg in 1765 and Lisbon in 1771, that was brought to the stage in the Eighteenth Century by an array of composers including Caldara, Hasse, Veracini, Gluck, Mysliveček, and, of course, Mozart. Sesto’s beautiful aria ‘Se mai senti spirarti sul volto’ is sung with eloquence shaped by the countertenor’s focused tones, the composer’s long phrases managed with admirable breath control. The character’s anguish throbs in Mineccia’s delivery of the words ‘son questi gli estremi sospiri del mio fido,’ but the response elicited by his vocalism is untroubled bliss.

First performed in Ludwigsburg in 1768, Jommelli’s La schiava liberata is the source of Don Garzia’s aria ‘Parto, ma la speranza,’ a beguiling number that Minecca sings handsomely, emphasizing the character’s ambivalence by being as attentive to rests as to notes. Here, too, the refinement of his technique is ably put to use, his noble phrasing complemented by his capacity for extending long lines without snatching breaths. Well-concealed discipline is also the core of Mineccia’s spontaneous-sounding performance of the title character’s aria ‘Salda rupe’ from Pelope, premièred in Stuttgart in 1755. The singer’s unpretentiously excellent diction in his native language is a trait that should not be taken for granted, especially in the performance of bravura music like Jommelli’s. Also noteworthy is Mineccia’s unfailing intelligence in embellishment: his ornamentation is restrained and musical, and he eschews the kind of overwrought cadenzas and tasteless above-the-stave interpolations that imperil the integrity of many singers’ performances of Eighteenth-Century repertory. The influence of Jommelli’s acquaintance with Hasse is particularly evident in ‘Salda rupe,’ and Mineccia’s confident, charismatic singing highlights the skill with which his countryman composed for the voice.

It was as a composer for the operatic stage that Jommelli was most appreciated during his lifetime, but he left to posterity a body of liturgically-themed work of equal significance. First performed in 1749 and known to have been admired by the musically astute Englishmen Charles Burney and Sir James Edward Smith, La passione di nostro signore Gesù Cristo is a superbly-crafted score, a setting of another of Metastasio’s widely-traveled texts that merits recognition as the equal of better-known versions by Caldara, Salieri, and Paisiello. Mineccia here sings Giovanni’s arias ‘Come a vista’ and ‘Ritornerà fra voi,’ both of which he distinguishes with elegant, unaffected vocalism. The music is overtly operatic, not unlike Caldara’s forward-lookingstilo galante, but Mineccia’s singing is noticeably more intimate here than in the opera arias. As he articulates them, the arias are effectively contrasted, their differing sentiments easily discerned by the listener.

Dating from 1750, Jommelli’s Cantata per la Natività della Beatissima Vergine is another work of high quality that should be more frequently performed, its lyricism no less captivating than that of Pergolesi’s familiar Stabat mater. Hypnotically propelled by guitar continuo, Speranza’s aria ‘Pastor son’io’ receives from Mineccia and Nereydas a reading of undiluted piety, one that exudes precisely what the archetype that utters it symbolizes: hope. Mineccia’s voice is here at its most purely beautiful, the seamless integration of his registers facilitating the poise of his singing. Jommelli’s 1751 Lamentazioni per il mercoledì santo perpetuated a tradition of music composed for Holy Week that was prevalent in Italy throughout the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, and the structure of the aria ‘O vos omnes’ suggests that Jommelli was aware of Alessandro Scarlatti’s standard-setting works for the Roman rites of settimana santa. Jommelli’s music combines simplicity and sophistication, and Mineccia sings it accordingly. Communication of the text is again the central focus of the singer’s endeavors, and he succeeds in conveying the sincere devotion of Jommelli’s writing.

In the course of The Jommelli Album, there are a few suspect pitches and instances in which passagework is attacked slightly too aggressively, but there is not one moment on this disc in which anything is faked or approximated. For many observers, Niccolò Jommelli’s name is likely to remain alongside those of throngs of his contemporaries as a notch on the timeline of opera between Händel and Mozart, but with The Jommelli Album Filippo Mineccia has given listeners a disc that makes Jommelli’s name one to remember. (NICCOLÒ JOMMELLI (1714 – 1774): The Jommelli Album – Arias for Alto—Filippo Mineccia, countertenor; Nereydas; Javier Ulises Illán, conductor [Recorded in Sala Gayarre, Teatro Real de Madrid, and Concert Hall of Escuela Municipal de Música de Pinto, Madrid, Spain, in May and December 2014; Pan Classics PC 10352) Joseph Newsome

Den Artikel entnahmen wir mit freundlicher Genehmigung dem hochinteressanten Blog des Autors: Voix des Arts, unbedingt lesenswert!

Der aus Bochum stammende derzeitigen Musikchef der Göteborgs Operan

Der aus Bochum stammende derzeitigen Musikchef der Göteborgs Operan

John Frandsen

John Frandsen

Dazu auch ein Auszug aus dem Artikel von Michael Wittmann, dem Herausgeber der Edition, im Booklet der neuen cpo-Ausgabe…

Dazu auch ein Auszug aus dem Artikel von Michael Wittmann, dem Herausgeber der Edition, im Booklet der neuen cpo-Ausgabe…

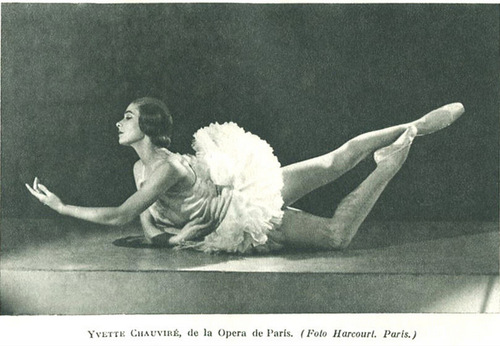

Ein Großmeister der Mélodies ist

Ein Großmeister der Mélodies ist

Autor

Autor