Abwechslung ist das halbe Leben, Veränderung auch – eine hochinteressante und wichtige Neuveröffentlichung von Niccolò Jommelis Arien for Alt (und es bleibt zu diskutieren, ob Alto oder Alt) aus der Sicht eines amerikanischen Kollegen, eben Joseph Newsome, der sich meiner Meinung nach in ebenso kundiger wie kritischer Sicht über Musik und musikalische Neuheiten auslässt; er ist eine willkommene Addition zu unseren beiden operalounge-Fachleuten fürs Barocke und für Counter. G. H.

Niccolò Jommelli/ Wikipedia

Many Twenty-First-Century opera lovers, influenced by the conventional wisdom of opera in the Eighteenth Century having been dominated before 1750 by Händel and after mid-century by Mozart, would likely be surprised to hear composers active after 1740 name as an eminent innovator among their colleagues the Neapolitan master Niccolò Jommelli. Born just north of Naples in the Campania commune of Aversa in 1714, Jommelli was a prodigious boy whose musical abilities were recognized and encouraged from an early age by his well-to-do family. Considering the powerful ecclesiastical and civic patronage that he enjoyed and the espousal of his abilities by as esteemed a composer as Johann Adolf Hasse, it is strange that so little verifiable information about Jommelli’s musical education and early career has survived. Many vital details of his life—his youthful conservatory studies, his presumed tuition under the celebrated Padre Martini, his tenure at Venice’s Ospedale degli Incurabili—can only be cited with footnotes and qualifiers that document the ironic lack of documentation. Like Johann Sebastian Bach and other composers whose biographies are compromised by empty pages, however, acquaintance with Jommelli is best made through his music. In his operatic homages to two of literature’s foremost abandoned heroines, Armida and Dido, Jommelli proved himself to be a musical dramatist of the first order; an order higher, in fact, than a number of composers whose scores have been revived in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries could claim to have achieved. Jommelli deserves champions among today’s best exponents of Eighteenth-Century repertory, and in the context of this engaging new release from Pan Classics, The Jommelli Album, he finds one in Italian countertenor Filippo Mineccia. A bold artist who shares the composer’s theatrical savvy, Mineccia here does for Jommelli what Dame Janet Baker did for Bach and Händel: the performances on this disc adhere to stylistic parameters that would have been familiar to Jommelli but do so in ways that appeal powerfully to the modern listener.

The performance of Jommelli’s Sinfonia a due violine e basso that serves as an interval of sorts, dividing the sequence of arias on The Jommelli Album into two intelligently-planned halves, is indicative of the high levels of virtuosity and expressivity reached in their playing on this disc by the musicians of Spanish period-instrument ensemble Nereydas. Directed by Javier Ulises Illán, the group’s exuberant playing enlivens the spirited numbers and enhances the mood of more contemplative pieces. In their playing of the Sinfonia, the opening Largo smolders with subdued intensity that erupts excitingly in the subsequent Fuga, its subject deftly handled by both composer and musicians. The same building and release of tension shape Nereydas’s performances of the Largo and Allegro movements that constitute the Sinfonia’s second part. The strings further the progress that has been made in historically-informed performances since the early days of scrawny, strident string playing, and the continuo work by harpsichordist María González and Robert Cases and Manuel Minguillón on theorbo and guitar provides a firm foundation for both instruments and voice. Whether the inclusion of the guitar in this music is wholly faithful to the milieux in which the sampled works were first performed may be questioned, but Jommelli’s Neapolitan origins permit this element of creative license, one which detracts nothing but adds a dimension of variety to the orchestral sound. Illán supports the dramatic vignettes that Mineccia creates in each aria with tempi that are expertly judged to showcase music and singer. Wherever his music was performed in the Eighteenth Century, Jommelli is unlikely to have heard playing better than that on this disc.

1753 was a year of great importance in Jommelli’s career as a composer of opera, and that annus mirabilis is represented on The Jommelli Album by arias from a pair of his most accomplished scores. Premièred in Torino, Bajazette was Jommelli’s contribution to the musical legacy of the eponymous Ottoman sultan’s confrontation with the legendary Tamburlaine, an operatic obsession of sorts that extended from Händel’s Tamerlano and Vivaldi’s pasticcio Bajazet to Mysliveček’s Il gran Tamerlano. From Bajazette, Mineccia sings Leone’s exacting ‘Fra il mar turbato,’ a simile aria as exhilaratingly evocative of its tempestuous text as any of Vivaldi’s celebrated arias in a similar vein. Braving the divisions with absolute confidence, Mineccia makes the aria a dramatic as well as a musical tour de force. The ease with which he ascends into his upper register, which occasionally leads to over-emphatic projection of tones at the crests of phrases, is reminiscent of the pioneering singing of Russell Oberlin. Like fellow countertenors Max Emanuel Cenčić and Franco Fagioli, Mineccia possesses the ability to convincingly evince masculinity whilst singing in a high register, and his technique enables him to devote considerable attention to subtleties of text and the composer’s setting of it. Also dating from 1753, in which year it was premièred in Stuttgart, the La clemenza di Tito excerpted here was Jommelli’s first treatment of the popular libretto by Metastasio, to which he would return with revised scores for Ludwigsburg in 1765 and Lisbon in 1771, that was brought to the stage in the Eighteenth Century by an array of composers including Caldara, Hasse, Veracini, Gluck, Mysliveček, and, of course, Mozart. Sesto’s beautiful aria ‘Se mai senti spirarti sul volto’ is sung with eloquence shaped by the countertenor’s focused tones, the composer’s long phrases managed with admirable breath control. The character’s anguish throbs in Mineccia’s delivery of the words ‘son questi gli estremi sospiri del mio fido,’ but the response elicited by his vocalism is untroubled bliss.

First performed in Ludwigsburg in 1768, Jommelli’s La schiava liberata is the source of Don Garzia’s aria ‘Parto, ma la speranza,’ a beguiling number that Minecca sings handsomely, emphasizing the character’s ambivalence by being as attentive to rests as to notes. Here, too, the refinement of his technique is ably put to use, his noble phrasing complemented by his capacity for extending long lines without snatching breaths. Well-concealed discipline is also the core of Mineccia’s spontaneous-sounding performance of the title character’s aria ‘Salda rupe’ from Pelope, premièred in Stuttgart in 1755. The singer’s unpretentiously excellent diction in his native language is a trait that should not be taken for granted, especially in the performance of bravura music like Jommelli’s. Also noteworthy is Mineccia’s unfailing intelligence in embellishment: his ornamentation is restrained and musical, and he eschews the kind of overwrought cadenzas and tasteless above-the-stave interpolations that imperil the integrity of many singers’ performances of Eighteenth-Century repertory. The influence of Jommelli’s acquaintance with Hasse is particularly evident in ‘Salda rupe,’ and Mineccia’s confident, charismatic singing highlights the skill with which his countryman composed for the voice.

It was as a composer for the operatic stage that Jommelli was most appreciated during his lifetime, but he left to posterity a body of liturgically-themed work of equal significance. First performed in 1749 and known to have been admired by the musically astute Englishmen Charles Burney and Sir James Edward Smith, La passione di nostro signore Gesù Cristo is a superbly-crafted score, a setting of another of Metastasio’s widely-traveled texts that merits recognition as the equal of better-known versions by Caldara, Salieri, and Paisiello. Mineccia here sings Giovanni’s arias ‘Come a vista’ and ‘Ritornerà fra voi,’ both of which he distinguishes with elegant, unaffected vocalism. The music is overtly operatic, not unlike Caldara’s forward-lookingstilo galante, but Mineccia’s singing is noticeably more intimate here than in the opera arias. As he articulates them, the arias are effectively contrasted, their differing sentiments easily discerned by the listener.

Dating from 1750, Jommelli’s Cantata per la Natività della Beatissima Vergine is another work of high quality that should be more frequently performed, its lyricism no less captivating than that of Pergolesi’s familiar Stabat mater. Hypnotically propelled by guitar continuo, Speranza’s aria ‘Pastor son’io’ receives from Mineccia and Nereydas a reading of undiluted piety, one that exudes precisely what the archetype that utters it symbolizes: hope. Mineccia’s voice is here at its most purely beautiful, the seamless integration of his registers facilitating the poise of his singing. Jommelli’s 1751 Lamentazioni per il mercoledì santo perpetuated a tradition of music composed for Holy Week that was prevalent in Italy throughout the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, and the structure of the aria ‘O vos omnes’ suggests that Jommelli was aware of Alessandro Scarlatti’s standard-setting works for the Roman rites of settimana santa. Jommelli’s music combines simplicity and sophistication, and Mineccia sings it accordingly. Communication of the text is again the central focus of the singer’s endeavors, and he succeeds in conveying the sincere devotion of Jommelli’s writing.

In the course of The Jommelli Album, there are a few suspect pitches and instances in which passagework is attacked slightly too aggressively, but there is not one moment on this disc in which anything is faked or approximated. For many observers, Niccolò Jommelli’s name is likely to remain alongside those of throngs of his contemporaries as a notch on the timeline of opera between Händel and Mozart, but with The Jommelli Album Filippo Mineccia has given listeners a disc that makes Jommelli’s name one to remember. (NICCOLÒ JOMMELLI (1714 – 1774): The Jommelli Album – Arias for Alto—Filippo Mineccia, countertenor; Nereydas; Javier Ulises Illán, conductor [Recorded in Sala Gayarre, Teatro Real de Madrid, and Concert Hall of Escuela Municipal de Música de Pinto, Madrid, Spain, in May and December 2014; Pan Classics PC 10352) Joseph Newsome

Den Artikel entnahmen wir mit freundlicher Genehmigung dem hochinteressanten Blog des Autors: Voix des Arts, unbedingt lesenswert!

Dazu auch ein Auszug aus dem Artikel von Michael Wittmann, dem Herausgeber der Edition, im Booklet der neuen cpo-Ausgabe…

Dazu auch ein Auszug aus dem Artikel von Michael Wittmann, dem Herausgeber der Edition, im Booklet der neuen cpo-Ausgabe…

Ein Großmeister der Mélodies ist

Ein Großmeister der Mélodies ist

Komponisten kommen nicht vor, und das mag man durchaus bedauern, insofern als gerade in der Charakterisierung der Autoren die musikalischen Ansichten Stendhals und namentlich seine Vergötterung von Cimarosa und Mozart viel plastischer hervortreten, als wenn er auf die Interpreten ihrer Musik eingeht. Der Wert seiner Eindrücke ist indes unbestritten. Stendhal ist zwar ein konservativer und im Grund intoleranter Musikliebhaber, der nur die italienische Oper des späten 18. Und frühen 19. Jh. gelten lässt, aber er hörte aufmerksam zu und konnte pointiert formulieren. Meistens handelt es sich dabei um Beobachtungen aus erster Hand, aber nicht immer. Bekanntlich nahm er es mit der ehrlichen Berichterstattung nicht ganz genau: seine Biographie Haydns ist ja ein erbärmliches Plagiat. Berühmtheit als Musikschriftsteller erlangte er jedoch vor allem mit seiner Vie de Rossini, die eine Hauptquelle Botaccins darstellt. Die Forscherin hat darüber hinaus eine Anzahl von anderen Texten exzerpiert, vor allem die Tagebücher und die Reiseberichte. Für jeden Künstler bietet das Piccolo dizionario eine kleine Lebensbeschreibung, eine Zusammenfassung von Stendhals Meinungen (dankenswerterweise erfolgt dies anhand von Zitaten in der Originalsprache und nicht in italienischer Übersetzung) und Angaben zu den Quellen. Man findet z.T. bekannte Passus über die Größen der Zeit wie Giovanni Battista Velluti (dem ja ein ganzes Kapitel in der Rossini-Biographie gewidmet ist), Andrea Nozzari oder Rosmunda Pisaroni. Diejenigen jedoch, die sich für das Primo Ottocento interessieren, werden sich vor allem für die Einträge zu Sängern zweiten und dritten Ranges interessieren, die anderswo wohl nicht so leicht greifbar sind. Der Rezensent könnte diese Publikation dementsprechend in höchsten Tönen loben, wenn sie nicht so schlampig erstellt worden wäre. Man kann vielleicht Bottacin nicht vorwerfen, dass das Büchlein keine Bilder enthält, welche die Veröffentlichung indes erheblich aufgewertet hätten, ja man könnte angesichts der zahlreichen Druckfehler noch wohlwollend ein Auge zudrücken. Gravierende Mängel dürfen jedoch nicht verschwiegen werden. Man sucht vergeblich eine richtige Bibliographie, auch der Werke Stendhals. Bottacin folgt der italienischen Unsitte, einen Titel das erste Mal vollständig zu zitieren, danach aber nur mit „cit.“ („zitiert“). Der Leser muss daher mühsam hin und her blättern, um die bibliographischen Angaben zu finden, die er braucht. Was vielleicht noch bei Monographien durchgeht, ist in einem Lexikon, das man bestimmt nicht von Anfang bis Ende liest, ein Ärgernis. Groteskerweise fehlt darüber hinaus ein Namenregister, was ein solches, an sich gut recherchiertes Werk, in dem natürlich zahlreiche, auch unbekanntere Komponisten und Werke genannt werden, beinahe unbrauchbar macht. Es scheint so, also ob – wie so oft – die Autorin kein genaues Bild ihres Publikums vor sich gehabt hätte. Denn wer soll sich heutzutage für dieses Thema, zumal im postberlusconischen Italien, interessieren, wenn nicht die conoscitori? Wie Stendhal in Mailand 1811 spürt der Leser hier gleichzeitig Dankbarkeit für das Unterfangen und die seccatura, die ein unzulänglicher Cicerone hervorruft

Komponisten kommen nicht vor, und das mag man durchaus bedauern, insofern als gerade in der Charakterisierung der Autoren die musikalischen Ansichten Stendhals und namentlich seine Vergötterung von Cimarosa und Mozart viel plastischer hervortreten, als wenn er auf die Interpreten ihrer Musik eingeht. Der Wert seiner Eindrücke ist indes unbestritten. Stendhal ist zwar ein konservativer und im Grund intoleranter Musikliebhaber, der nur die italienische Oper des späten 18. Und frühen 19. Jh. gelten lässt, aber er hörte aufmerksam zu und konnte pointiert formulieren. Meistens handelt es sich dabei um Beobachtungen aus erster Hand, aber nicht immer. Bekanntlich nahm er es mit der ehrlichen Berichterstattung nicht ganz genau: seine Biographie Haydns ist ja ein erbärmliches Plagiat. Berühmtheit als Musikschriftsteller erlangte er jedoch vor allem mit seiner Vie de Rossini, die eine Hauptquelle Botaccins darstellt. Die Forscherin hat darüber hinaus eine Anzahl von anderen Texten exzerpiert, vor allem die Tagebücher und die Reiseberichte. Für jeden Künstler bietet das Piccolo dizionario eine kleine Lebensbeschreibung, eine Zusammenfassung von Stendhals Meinungen (dankenswerterweise erfolgt dies anhand von Zitaten in der Originalsprache und nicht in italienischer Übersetzung) und Angaben zu den Quellen. Man findet z.T. bekannte Passus über die Größen der Zeit wie Giovanni Battista Velluti (dem ja ein ganzes Kapitel in der Rossini-Biographie gewidmet ist), Andrea Nozzari oder Rosmunda Pisaroni. Diejenigen jedoch, die sich für das Primo Ottocento interessieren, werden sich vor allem für die Einträge zu Sängern zweiten und dritten Ranges interessieren, die anderswo wohl nicht so leicht greifbar sind. Der Rezensent könnte diese Publikation dementsprechend in höchsten Tönen loben, wenn sie nicht so schlampig erstellt worden wäre. Man kann vielleicht Bottacin nicht vorwerfen, dass das Büchlein keine Bilder enthält, welche die Veröffentlichung indes erheblich aufgewertet hätten, ja man könnte angesichts der zahlreichen Druckfehler noch wohlwollend ein Auge zudrücken. Gravierende Mängel dürfen jedoch nicht verschwiegen werden. Man sucht vergeblich eine richtige Bibliographie, auch der Werke Stendhals. Bottacin folgt der italienischen Unsitte, einen Titel das erste Mal vollständig zu zitieren, danach aber nur mit „cit.“ („zitiert“). Der Leser muss daher mühsam hin und her blättern, um die bibliographischen Angaben zu finden, die er braucht. Was vielleicht noch bei Monographien durchgeht, ist in einem Lexikon, das man bestimmt nicht von Anfang bis Ende liest, ein Ärgernis. Groteskerweise fehlt darüber hinaus ein Namenregister, was ein solches, an sich gut recherchiertes Werk, in dem natürlich zahlreiche, auch unbekanntere Komponisten und Werke genannt werden, beinahe unbrauchbar macht. Es scheint so, also ob – wie so oft – die Autorin kein genaues Bild ihres Publikums vor sich gehabt hätte. Denn wer soll sich heutzutage für dieses Thema, zumal im postberlusconischen Italien, interessieren, wenn nicht die conoscitori? Wie Stendhal in Mailand 1811 spürt der Leser hier gleichzeitig Dankbarkeit für das Unterfangen und die seccatura, die ein unzulänglicher Cicerone hervorruft

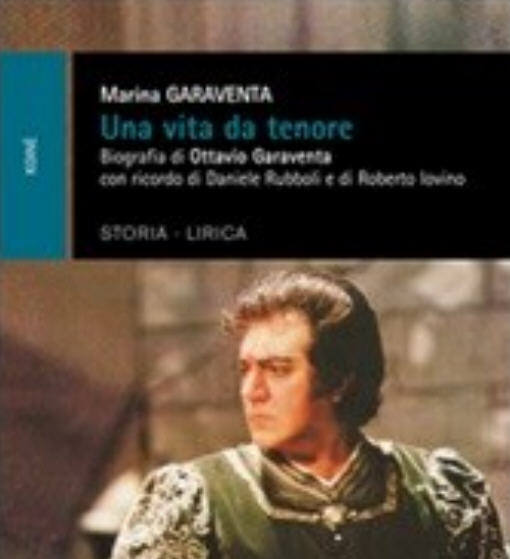

In seinem Vorwort beklagt Roberto Iovino, wie schwer es heute Journalisten wie er haben, Artikel über klassische Musik in Tageszeitungen unterzubringen, was man als Leser des Corriere della Sera eigentlich nicht bestätigen kann. Er lobt die Bodenständigkeit seines Freundes Garaventa, dessen 80. Geburtstag nicht genügend gewürdigt wurde und der zu gut dafür war, eine erfolgreiche politische Karriere zu machen. Als Sänger hingegen gelang es ihm, zunächst als Bariton, später als Tenor, den Concorso Aslico zweimal zu gewinnen, in Busseto der Beste von 380 Bewerbern um den Ersten Preis gewesen zu sein.

In seinem Vorwort beklagt Roberto Iovino, wie schwer es heute Journalisten wie er haben, Artikel über klassische Musik in Tageszeitungen unterzubringen, was man als Leser des Corriere della Sera eigentlich nicht bestätigen kann. Er lobt die Bodenständigkeit seines Freundes Garaventa, dessen 80. Geburtstag nicht genügend gewürdigt wurde und der zu gut dafür war, eine erfolgreiche politische Karriere zu machen. Als Sänger hingegen gelang es ihm, zunächst als Bariton, später als Tenor, den Concorso Aslico zweimal zu gewinnen, in Busseto der Beste von 380 Bewerbern um den Ersten Preis gewesen zu sein.

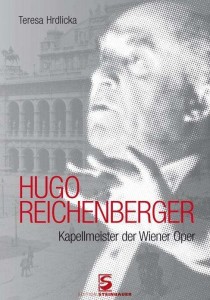

Interessant ist Reichenberger für den heutigen Leser auch durch seine Nähe zu Richard Strauss und Gustav Mahler, durch die Gäste, die er nach den Stationen München und Frankfurt in Wien zu betreuen hatte, so Caruso, oder deren Ensemblemitglieder wie die Jeritza oder zeitweise Slezak. Das Ringen um die endgültige Fassung der Ariadne auf Naxos gehört zu den aufschlussreichsten Kapiteln des Buches, und wer wusste schon, dass die Ensemblemitglieder zur Traviata, damals als Violetta auf dem Spielplan, ihre eigenen Abendgarderoben mitbringen mussten. Zu den Aufgaben des Dirigenten gehörte auch die Beurteilung von neu eingereichten Opern, wobei sich Reichenberger in Bezug auf Puccinis Fanciulla ein krasses Fehlurteil leistete. Übrigens gab es bereits vor dem 1. Weltkrieg in Wien den Merker, aus dem die Verfasserin zitiert, ebenso aus den Artikeln von Julius Korngold, Vater des Komponisten, der Reichenberger nicht besonders wohlgesonnen war.

Interessant ist Reichenberger für den heutigen Leser auch durch seine Nähe zu Richard Strauss und Gustav Mahler, durch die Gäste, die er nach den Stationen München und Frankfurt in Wien zu betreuen hatte, so Caruso, oder deren Ensemblemitglieder wie die Jeritza oder zeitweise Slezak. Das Ringen um die endgültige Fassung der Ariadne auf Naxos gehört zu den aufschlussreichsten Kapiteln des Buches, und wer wusste schon, dass die Ensemblemitglieder zur Traviata, damals als Violetta auf dem Spielplan, ihre eigenen Abendgarderoben mitbringen mussten. Zu den Aufgaben des Dirigenten gehörte auch die Beurteilung von neu eingereichten Opern, wobei sich Reichenberger in Bezug auf Puccinis Fanciulla ein krasses Fehlurteil leistete. Übrigens gab es bereits vor dem 1. Weltkrieg in Wien den Merker, aus dem die Verfasserin zitiert, ebenso aus den Artikeln von Julius Korngold, Vater des Komponisten, der Reichenberger nicht besonders wohlgesonnen war.

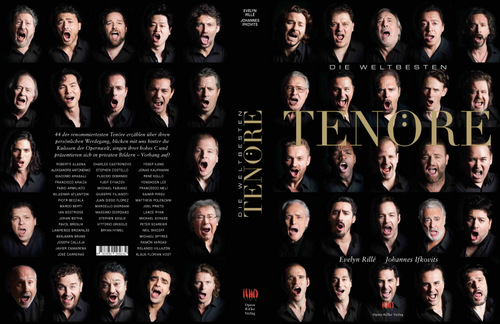

Mehr oder weniger hohes C – Die weltbesten Tenöre:

Mehr oder weniger hohes C – Die weltbesten Tenöre:

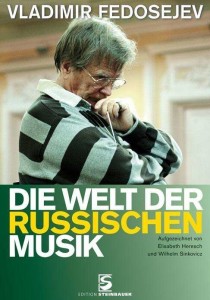

Da geht es um Interpretation, die nach Meinung des Dirigenten die Ausführung des Willens des Komponisten plus die Intuition des Interpreten sein sollte, die ihrerseits wieder von der Zeit, in der dieser lebt, geprägt sein wird. Es geht um das Problem der unterschiedlichen Fassungen eines Werks, insbesondere am Beispiel des Boris Godunov, den beiden von Musorgskij selbst stammenden und denen von Rimski-Korsakov und Schostakowitsch nachgewiesen, und um die Tatsache, dass ein Komponist nicht unbedingt ein guter Interpret seines Werkes sein muss, was ebenfalls mit Beispielen belegt wird. Beklagt wird das allmähliche Verschwinden der klassischen Musik aus dem gesellschaftlichen Leben, besonders des Russlands, seiner Amerikanisierung, der fehlende Musikunterricht, das Vorherrschen einer „Pop- und Eventkultur“. Diktatoren wie Stalin und Hitler wird zugute gehalten, dass sie trotz aller Repressalien doch für eine Blüte der Kultur in ihren Ländern sorgten. Die schwindende Bedeutung der Religion bedeutet nach Fedosejev auch einen Verlust an Kultur, „eine Verarmung der Seele“. Kritisiert werden die Vertreter der Hochkultur, die ihren Erfolg der Tatsache verdanken, dass sie sich „attraktiv (zu) präsentieren“ verstehen. Ob damit etwa ein deutscher Geiger und ein deutscher Tenor gemeint sind?

Da geht es um Interpretation, die nach Meinung des Dirigenten die Ausführung des Willens des Komponisten plus die Intuition des Interpreten sein sollte, die ihrerseits wieder von der Zeit, in der dieser lebt, geprägt sein wird. Es geht um das Problem der unterschiedlichen Fassungen eines Werks, insbesondere am Beispiel des Boris Godunov, den beiden von Musorgskij selbst stammenden und denen von Rimski-Korsakov und Schostakowitsch nachgewiesen, und um die Tatsache, dass ein Komponist nicht unbedingt ein guter Interpret seines Werkes sein muss, was ebenfalls mit Beispielen belegt wird. Beklagt wird das allmähliche Verschwinden der klassischen Musik aus dem gesellschaftlichen Leben, besonders des Russlands, seiner Amerikanisierung, der fehlende Musikunterricht, das Vorherrschen einer „Pop- und Eventkultur“. Diktatoren wie Stalin und Hitler wird zugute gehalten, dass sie trotz aller Repressalien doch für eine Blüte der Kultur in ihren Ländern sorgten. Die schwindende Bedeutung der Religion bedeutet nach Fedosejev auch einen Verlust an Kultur, „eine Verarmung der Seele“. Kritisiert werden die Vertreter der Hochkultur, die ihren Erfolg der Tatsache verdanken, dass sie sich „attraktiv (zu) präsentieren“ verstehen. Ob damit etwa ein deutscher Geiger und ein deutscher Tenor gemeint sind?

, stammt ebenfalls aus Deutschkreutz, welches leicht übertreibend als „jüdische Gemeinde“ bezeichnet wird. Aber immerhin war mehr als ein Drittel der Einwohner zu Goldmarks Zeiten jüdischer Abstammung

, stammt ebenfalls aus Deutschkreutz, welches leicht übertreibend als „jüdische Gemeinde“ bezeichnet wird. Aber immerhin war mehr als ein Drittel der Einwohner zu Goldmarks Zeiten jüdischer Abstammung