Die Rysanek als Brünnhilde? Das war zunächst nur ein Gerücht. Wer sich schließlich den sündhaft teuren Bildband über die Sängerin leisten konnte, der 1990 bei Hoffmann und Campe herausgekommen war, wusste es aber bald genau: Eher beiläufig war dort in der Diskographie eine Schallplatte mit den Tonaufnahmen aus dem (auch im deutschen Fernsehen gezeigten) Film Frauen um Richard Wagner nach dem Roman Magic Fire von Bertita Harding aufgeführt. Das Label? STV. Das klang nach limitierter Privat-Club-Pressung. Und so ist es auch! Inzwischen wurde die LP bei eben dieser Club-Firma auf CD umgeschnitten und wiederum in einer Edition von tausend Exemplaren auf den Markt gebracht. Nicht nur das. Das Label Filmjuwelen zog dann mit dem Film gleich nach – nun mit dem Titel Magic Fire – Die Richard Wagner Story.

Alles Warten hat sich gelohnt. Die Rysanek als Brünnhilde ist jedoch leicht übertrieben. Da gibt es einen kleinen Ausschnitt aus dem Schlussgesang der Götterdämmerung, die letzten zehn Zeilen von „Fühl‘ meine Brust auch“. Lohnt sich das? Es lohnt sich! Aufgenommen wurde 1955. Die Rysanek begann gerade ihre große internationale Karriere, in der die Brünnhilde aber nicht vorkommen sollte. Was damals leicht, leuchtend und sehr vielversprechend klang, war abgetrotzt. Ganz sicher wäre diese Sängerin nicht so lange im Geschäft geblieben, hätte sie eine hochdramatische Richtung eingeschlagen. Am Ende ist so eine kurze Sequenz vielleicht doch mehr wert als hundert Mitschnitte als Brünnhilde, wäre es denn dazu gekommen. Die Fans können sich verzehren. Ach, hätte sie doch… Sie hat nicht und das war sehr klug.

Alles Warten hat sich gelohnt. Die Rysanek als Brünnhilde ist jedoch leicht übertrieben. Da gibt es einen kleinen Ausschnitt aus dem Schlussgesang der Götterdämmerung, die letzten zehn Zeilen von „Fühl‘ meine Brust auch“. Lohnt sich das? Es lohnt sich! Aufgenommen wurde 1955. Die Rysanek begann gerade ihre große internationale Karriere, in der die Brünnhilde aber nicht vorkommen sollte. Was damals leicht, leuchtend und sehr vielversprechend klang, war abgetrotzt. Ganz sicher wäre diese Sängerin nicht so lange im Geschäft geblieben, hätte sie eine hochdramatische Richtung eingeschlagen. Am Ende ist so eine kurze Sequenz vielleicht doch mehr wert als hundert Mitschnitte als Brünnhilde, wäre es denn dazu gekommen. Die Fans können sich verzehren. Ach, hätte sie doch… Sie hat nicht und das war sehr klug.

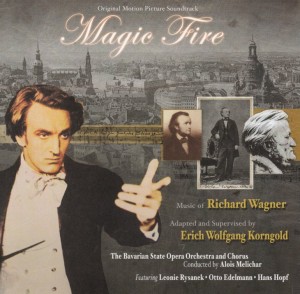

Im krachbunten Film ist die Musik einem Schnelldurchlauf der ersten geschlossenen Aufführung des Ring des Nibelungen 1976 in Bayreuth untergelegt. Mit echtem Pferd Grane, reitenden Walküren und der finalen Katastrophe, bei der die Balken der Gibichungenhalle in den Flammen des Weltenbrandes zusammenkrachen. So dürfte das vorher und nachher nie auf einer Bühne zu sehen gewesen sein. Musikalisch ist das Potpourri nur machbar, weil Erich Wolfgang Korngold das Original den filmischen Erfordernissen angepasst hat. Das klingt flott, irgendwie anders, und ist doch immer Wagner. Korngold hat Respekt vor dessen Musik, jubelt nichts Eigenes unter. Sein Werk ist das Arrangement. Davon versteht er sehr viel. Einige fremde Zutaten beziehen ihre Verwendung aus der Handlung des Films. Als Wagner das erste Mal nach Paris kommt, mischt sich die Marseillaise unter den Fliegenden Holländer, den er noch als Idee in der Tasche hatte. Bei der zum königlichen Lever aufgebauschten ersten Begegnung des armen Schluckers aus Deutschland mit dem gefeierter Giacomo Meyerbeer, den Wagner als scharfen Widersacher empfand, umschmeichelt Musik aus den Hugenotten das Ohr.

Im krachbunten Film ist die Musik einem Schnelldurchlauf der ersten geschlossenen Aufführung des Ring des Nibelungen 1976 in Bayreuth untergelegt. Mit echtem Pferd Grane, reitenden Walküren und der finalen Katastrophe, bei der die Balken der Gibichungenhalle in den Flammen des Weltenbrandes zusammenkrachen. So dürfte das vorher und nachher nie auf einer Bühne zu sehen gewesen sein. Musikalisch ist das Potpourri nur machbar, weil Erich Wolfgang Korngold das Original den filmischen Erfordernissen angepasst hat. Das klingt flott, irgendwie anders, und ist doch immer Wagner. Korngold hat Respekt vor dessen Musik, jubelt nichts Eigenes unter. Sein Werk ist das Arrangement. Davon versteht er sehr viel. Einige fremde Zutaten beziehen ihre Verwendung aus der Handlung des Films. Als Wagner das erste Mal nach Paris kommt, mischt sich die Marseillaise unter den Fliegenden Holländer, den er noch als Idee in der Tasche hatte. Bei der zum königlichen Lever aufgebauschten ersten Begegnung des armen Schluckers aus Deutschland mit dem gefeierter Giacomo Meyerbeer, den Wagner als scharfen Widersacher empfand, umschmeichelt Musik aus den Hugenotten das Ohr.

Ein blonder Franz Liszt (Carlos Tompson) und seine strenge Tochter Cosima (Rita Gam)

Biographisch folgt der Film zwar den wichtigsten Ereignissen im Leben Richard Wagners, die Einzelheiten sind oft ziemlich frei gestaltet und streifen den Kitsch. So wurde das „Siegfried-Idyll“ ja nicht etwa kurz nach der Geburt des Stammhalters in Triebschen aufgeführt, sondern erst ein Jahr später in Erinnerung an das freudige Ereignis. Dar Tod in Venedig ereilt Wagner bekanntlich auch ganz anders als im Film, wo er im Beisein von Frau Cosima und Franz List am Flügel Parsifal spielend mit verklärtem Blick gen Himmel fast unmerklich den Geist aufgibt. In Hollywood werden halt Lebensläufe nach eigenen Gesetzen in Szene gesetzt. Wer sich auf den Film einlässt, weiß das. Die Hauptrolle spielt ohnehin die Musik. Die Rysanek muss auch noch die Senta und die Sieglinde geben, Partien, die sie tatsächlich im Repertoire hatte. Neben ihr wirkt noch der junge Hans Hopf episodisch als Tannhäuser, Siegmund und Walter von Stolzing, während Otto Edelmann für Holländer, Hans Sachs und Wotan zuständig ist.

König Ludwig II. (Gerhard Riedmann) steht vor seinem Meister Richard Wagner (Alan Badel)

Wie damals üblich in solchen Musiker-Biographie-Filmen – es gab jede Menge davon –, werden die Sänger im Vorspann nicht namentlich genannt. Sie sind nur pauschal aufgeführt gemeinsam mit dem Chor und Orchester der Bayerischen Staatsoper unter der Leitung von Alois Melichar. Dieser hatte nur eine kurze Karriere als Dirigent. Sein Gebiet war die Filmmusik – beispielsweise für „Mutterlied“ mit Maria Cebotari und Benjamino Gigli. Auch ausgesprochene Nazipropagandafilme wie „…reitet für Deutschland“ und „Kameraden“ (beide 1941) finden sich in seinem Werkverzeichnis. Umso erstaunlicher ist es, dass er 1955 für einen US-amerikanischen Streifen herangezogen wurde, wenn auch nur als Dirigent. Genaue Angaben zu den mitwirkenden Sängern liefert die CD, die bei Amazon noch zu haben ist. In den 26 Tracks sind alle Szenen aufgelistet, in denen Musik erklingt – und zwar mit genauem Bezug zum jeweiligen Werk und den Mitwirkenden. Zu erfahren ist auch, dass Korngold selbst für Wagner das Klavier spielt, als der sich von dieser Welt verabschiedet. Rüdiger Winter

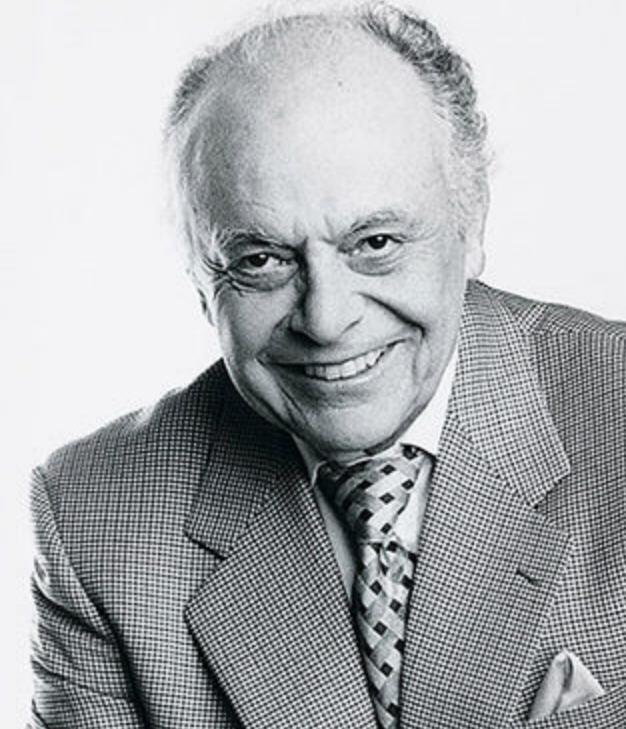

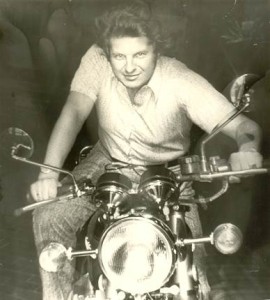

Produzent des Albums ist übrigens George Korngold, der 1928 geborene Sohn des Komponisten, der jetzt selbst zu Wort kommen soll. Den nachfolgenden Artikel im originalen Englisch entnahmen wir dem Booklet zur oben genannten CD, daraus auch das Schwarz-Weiß-Foto. Die Farbfotos stammen aus dem Film.

„The Lord of the Ring – In early 1954 William Dieterle, the respected film director and an old family friend, approached my father, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, with the idea of supervising and adapting the music of Richard Wagner for his production of Magic Fire, the biography of Wagner’s life, to be shot entirely on location in Germany It had long been Dieterle’s dream to bring Wagner’s life to the screen and Republic Pictures had decided to finance the film from monies frozen in German banks after World War II, monies they could not otherwise transfer to the U.S. Famous for his film-biographies, Dr. Ehlrich’s Magic Bullet, The Life of Emil Zola and Juarez (the latter with music by my father), all highly distinguished and acclaimed motion pictures, Dieterle was the logical choice to attempt dramatization of the life and career of the great German composer.

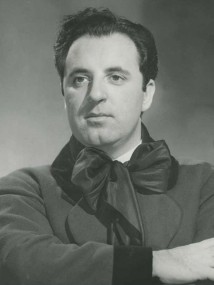

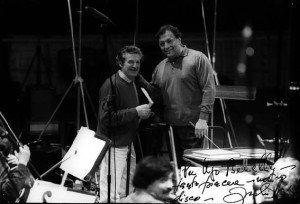

Erich Wolfgang Korngold gibt dem Wagner-Darsteller Alan Badel Dirigierunterricht/Magic Fire

The screenplay was written by Bertita Harding, based on her book Magic Fire in collaboration with Dieterle (he wrote under the pseudonym of David Chantler) and E.A. Dupont, the renowned German film director. The scenario was long, wordy and Germanic, and tried to cover too much of Wagner’s life, but it was factual and left room to present a large „sampling“ of Wagner’s music without interruption by dialogue or action. My father had retired from films in 1947 to return to composition for the concert and opera stages and had refused many offers to compose music for motion pictures. After first turning Dieterle down, he finally decided to take on the difficult task of adapting Wagner’s music because he was afraid that in less devoted hands the composer’s music would suffer the same fate as had that of many other great musicians whose lives had been brought to the screen by Hollywood.

Republic, known for its productions of low-budget „westerns,“ was not exactly the ideal choice to undertake such a serious project, but they had indeed previously ventured into the field of respectable, prestige films (The Quiet Man) and Dieterle felt he could make the film under their aegis, provided he was allowed a free hand as promised. The conditions for my father’s participation were ideal. He would be free to choose repertoire, artists, orchestra, chorus and the recording venue, and his wishes in music/dramatic matters were to be adhered to without any interference. Then and only then did he accept the offer.

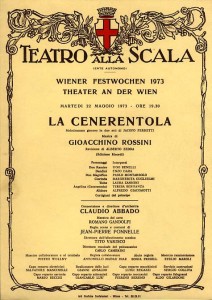

„Magic Fire“: Alan Badel als Wagner/Magic Fire CD

At the time, I was a recording engineer in a small studio in Hollywood, trying to break into the motion picture industry — an almost impossible „Catch-22“ proposition, as in order to be hired by a film studio, you had to be a member of the union, and in order to join the union, you had to have been hired by a studio! As a last resort, I decided to resign from my engineering job and go to Germany in the hope that there – without union restrictions – I might be hired to work on Magic Fire. As it turned out I was finally given a job as an apprentice film cutter to Stan Johnson, the well-known film editor, from whom I learned film editing from the ground up. I later became the music editor on the film, the only film I ever worked on with my father, and eventually mixed the music during the final re-recording of the music, sound effects and dialogue. Shooting Magic Fire began in late August 1954, in Schwetzingen, Germany, a small German town equally famous for its white asparagus as for the fact that it boasted one of the few remaining undamaged baroque Court-Theatres. The Lohengrin sequence was filmed there with over 1,000 dress-extras in the audience. I was in charge of the „playbacks,“ entire musical sequences previously recorded in Munich to which the actor-singers mouthed the singing and an orchestra „played.“

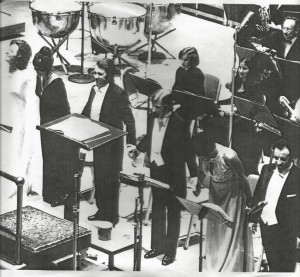

Das Finale der nachgestellten Uraufführung der „Meistersinger von Nürnberg“ in München/Magic Fire

Suddenly it was discovered that director Dieterle had forgotten his white gloves, without which he absolutely refused to begin shooting any film. He was quite superstitious and also firmly believed in astrology, having signed his contract for Magic Fire at exactly 5:22 a.m. on the day prescribed by his astrologer, thus apparently ensuring the film’s success! A messenger was dispatched to Heidelberg to find white gloves, and when he finally returned, after four hours, shooting could begin. In the meantime, the entire crew, the stars and the extras had waited patiently and the production manager, Lee Lukather, a veteran of Republic westerns, who hated this film and in particular the music which „… cost a bundle …,“ ranted at the loss of time and money (Ironically, this rough and tough man, who only came into his own when real horses were used during the shooting of the Ride of the Valkyries, developed an almost touching attachment to my father.)

This had not been a very auspicious beginning, but nevertheless things began to improve immediately, with Dieterle pushing ever forward with the complicated shooting schedule, which included such locations as the delicately imposing Mark Grafliche Theatre in Bayreuth (Der Fliegende Hollander sequence), the Wagner Festspielhaus in Bayreuth (Der Ring des Nibelungen montage), and the Bavarian State Opera in the Prinz Regenten Theatre in Munich (Die Meistersinger excerpts). While shooting in the Bayreuth Festspielhaus it was discovered that the actor who was to portray the conductor, Hans Richter, had not shown up on the set and Dieterle appealed to my father to take his place so that the filming of the difficult Ring sequences could commence. Dressed in tails and made up with a beard and wig, my father thus made his second cinematic appearance „conducting“ the Ring! (He had previously appeared playing the piano in a short film about the making of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1934). the music is the socalled „foreign track,“ a recording made without dialogue to be sent to foreign countries so that they can „dub“ in their respective languages. Thus, many pieces either end abruptly, reflect some „perspective“ effect, or are faded at the end to accommodate changing visual scenes and deletions from the original version. As was his custom, my father played all the solo piano parts, as he had done in all his previous films where called for. Due to ill health, he was not allowed to conduct the music and Alois Melichar, a name undoubtedly familiar to collectors of early Deutsche Grammophon records, where he was a respected chief conductor, was asked to conduct. Their collaboration led to a lasting friendship and Melichar later went on to conduct the first broadcast performance of Korngold’s Symphony in F in Graz, Austria.

Alan Badel hat als Richard Wagner von seinem musikalischen Mentor Korngold viel gelernt/Magic Fire

Throughout the filming of Magic Fire, my father began to see more and more of his „dreams“ fading. And when we watched the first screening of the rough-cut film, he turned to me with a twinkle in his eye and whispered: „… perhaps Dieterle should have signed his contract at 6:30 in the morning!“ Later, as the film was being shortened more and more, he nevertheless kept his undaunted good humor and once remarked that „… when I had to compress 16 hours of the Ring into five minutes, that was already drastic, but now that they have cut it down to four minutes – that’s too much…“ In the end, Magic Fire, already damaged by a weak script and a not all too awe-inspiring cast, could not survive. Unfortunately, despite a heroic performance by Alan Badel as Wagner, the beautiful camera work of Ernest Haller (Gone with the Wind) and the grand music of Wagner, it was not strong enough to withstand the tamperings of Hollywood executives. It was releasedor, as one of the members of the staff quipped, it „escaped“ – in late 1955 and quickly disappeared, to surface years later on late-night television.

Melodramatisches Ende: Cosima (Rita Gam) am Fenster des Palazzo Vendramin, wo Wagner 1883 starb/Magic Fire

The worthwhile efforts of many talents – Dieterle, Korngold, Badel, the great young singers Leonie Rysanek, Otto Edelmann and Hans Hopf – had come to naught, partially due to the almost impossible task of condensing the career of a larger-than-life historic figure to a couple of hours, but mostly because once again, despite firm assurances to the contrary, the film ended up in the hands of persons with very little artistic integrity. When viewed today it has become a series of cliches, and even the music, which my father strived so hard to preserve, is disrespectfully decimated. Unfortunately, not all of the original music sequences, which would have better evidenced the artistic intent of the project, are in existence anymore. Hopefully, the version presented on this record, though already from an earlier, slightly cut fourth generation master, will serve to remind what Magic Fire might have been.“

Magic Fire – Die Richard Wagner Story. USA 1955, Regie: William Dieterle, 103 Minuten, Mitwirkende: Alan Badel (Richard Wagner), Yvonne de Carlo (Minna), Carlos Tompson (Franz Liszt), Rita Gam (Cosima), Gerhard Riedmann (Ludwig II.) und viele andere. Label: Fernsehjuwelen, Bestellnummer 6414361.

Zeitgleich ist der Mehrteiler „Giuseppe Verdi – Eine italienische Legende“ bei Filmjuwelen herausgekommen, der wesentlich genauer mit der Biographie des Komponisten umgeht als der Wagner-Film mit seinem Helden. Dafür gibt es auch mehr Zeit. Es werden alle wesentlichen Stationen im Leben und Schaffen Verdi in teils grandiosen Bildern abgehandelt. Der Film lebt von diesen farbenprächtigen Einstellungen, die das Team an viele Originalschauplätze führte, bis hin in die Sowjetunion. Dabei wurde nicht gespart. Kostüme, Make-up und Ausstattung sind ihrer Zeit so genau nachempfunden, wie man das sonst nur aus englischen BBC-Serien kennt. Auch diese Produktion richtet sich an ein breites Publikum, hält aber stets darauf, das sich auch jene angesprochen fühlen dürfen, die mit Werk und Lebens Verdi sehr gut vertraut sind. Nicht mehr und nicht weniger will der Film sein. In Gesangsszenen erklingen die Stimmen von Maria Callas und Luciano Pavarotti. In Italien war die Serie ein riesiger Erfolg, ähnlich einem Straßenfeger. Den „Cable ACE Award“ gab es in den USA. Als der Film im Sommer 1983 ins Programm der ARD gehoben wurde, spottete das Nachrichtenmagazin „Der Spiegel“: „In einer aufwendigen Fernsehserie hat nun der italienische Regisseur und Drehbuchautor Renato Castellani den Komponisten wieder zum Leben erweckt.“ Mit dem Abspielen seiner Gassenhauer illustriere Castellani dabei vor allem die Bedeutung Verdis für das „Wunschkonzert-Publikum“. Übrigens fand die deutsche Erstaufführung gleich nach Fertigstellung der Serie im DDR-Fernsehen statt. Rüdiger Winter

Zeitgleich ist der Mehrteiler „Giuseppe Verdi – Eine italienische Legende“ bei Filmjuwelen herausgekommen, der wesentlich genauer mit der Biographie des Komponisten umgeht als der Wagner-Film mit seinem Helden. Dafür gibt es auch mehr Zeit. Es werden alle wesentlichen Stationen im Leben und Schaffen Verdi in teils grandiosen Bildern abgehandelt. Der Film lebt von diesen farbenprächtigen Einstellungen, die das Team an viele Originalschauplätze führte, bis hin in die Sowjetunion. Dabei wurde nicht gespart. Kostüme, Make-up und Ausstattung sind ihrer Zeit so genau nachempfunden, wie man das sonst nur aus englischen BBC-Serien kennt. Auch diese Produktion richtet sich an ein breites Publikum, hält aber stets darauf, das sich auch jene angesprochen fühlen dürfen, die mit Werk und Lebens Verdi sehr gut vertraut sind. Nicht mehr und nicht weniger will der Film sein. In Gesangsszenen erklingen die Stimmen von Maria Callas und Luciano Pavarotti. In Italien war die Serie ein riesiger Erfolg, ähnlich einem Straßenfeger. Den „Cable ACE Award“ gab es in den USA. Als der Film im Sommer 1983 ins Programm der ARD gehoben wurde, spottete das Nachrichtenmagazin „Der Spiegel“: „In einer aufwendigen Fernsehserie hat nun der italienische Regisseur und Drehbuchautor Renato Castellani den Komponisten wieder zum Leben erweckt.“ Mit dem Abspielen seiner Gassenhauer illustriere Castellani dabei vor allem die Bedeutung Verdis für das „Wunschkonzert-Publikum“. Übrigens fand die deutsche Erstaufführung gleich nach Fertigstellung der Serie im DDR-Fernsehen statt. Rüdiger Winter

Giuseppe Verdi – Eine italienische Legende, Ko-Produktion zwischen Italien, Frankreich, Deutschland, England, Schweden und der Sowjetunion 1982, 529 Minuten in acht Teilen, Regie: Renato Castellani. Mitwirkende: Ronald Pickup (Giuseppe Verdi), Carla Fracci (Giuseppina Strepponi), Giampiero Albertini (Antonio Berezzi), Lino Capolicchio (Arrigo Boito), Eva Christian (Teresa Stolz), Daria Nicolodi (Margherita Barezzi), Jan Niklas (Angelo Mariani), Nino Dal Fabbro (Giulio Ricordi) und viele andere. Label: Fernsehjuwelen, Bestellnummer: 6414274.

Alle beziehen sich auf antike Dramen:

Alle beziehen sich auf antike Dramen: