Erst seit der Rossini-Renaissance in Pesaro ab 1985 ist eigentlich auch der Name seiner ersten Frau, Isabella Colbran, über die bloße Nennung als Rossini-Interpretin in das heutige Bewusstsein gerückt – jene Sängerin, die mit ihrer dunkel timbrierten Sopranstimme ihn zu den herrlichen Opern wie Otello oder Armida inspirierte. Wer war sie? Eigentlich kennt man sie nur als Anhängsel Rossinis, der sie von dem Intendanten (Domenico Barbaja) des San Carlo in Neapel „übernahm“, erstaunlicherweise sogar heiratete und für den sie für eine gewisse Zeit zur Muse wurde.

Den Begriff Mezzosopran gab es da noch nicht, nur Sopran I /prima donna und II/seconda donna sowie alto, aber es ist nach Lage der Noten kein Zweifel daran, dass die Colbran ein dunkler Sopran war, ähnlich dem Falcon in Frankreich nach der Sängerin Cornelie Falcon, eben ein kurzer Sopran mit guter Tiefe. In moderner Zeit sind das Stimmen wie die der Cecilia Gasdia oder Anna Caterina Antonacci mit ihrem leidvoll-poetischen Timbre – ein wirklicher im oberen Bereich knapper Sopran voller Poesie und nicht das energisch-tüchtige Geratter einer Joyce Di Donato ohne Charme und Kern oder die angestrengte Hochleistungsbalance einer Cecilia Bartoli (ich weiß, ich handele mir jetzt einen Sturm der Entrüstung ein). Die Colbran schuf einen neuen Stimmtyp und war für Rossini das ideale Instrument zum Ausdruck seiner zunehmenden Hinwendung zu Menschlichkeit voller dunkler Tragik. Mit der Trennung von der Colbran wandte sich Rossini anderen Stimmen zu und die Aufteilung in Kategorien, wie wir sie heute spätestens seit Verdi kennen (der das klassische Quartett Sopran/Mezzosopran/Tenor/Bariton „erfand“), bahnte sich mit Bellini und Donizetti an (wenngleich auch Donizetti durchaus an dem stimmlich flexiblen Modell der beiden Soprane festhielt und sich für Bellinis Norma die Damen durchaus abwechselten als Norma und Adalgisa, was als Karikatur später in unserer Zeit das Tandem Verrett-Bumbry oder auch Sutherland-Caballé vorführte, letztere beide Normas von Rang). Rossini liebte die dunklen Stimmen, und seine frühen Opern sind voll mit Partien für schnurrbärtige Altistinnen in der Folge der Kastraten – nicht umsonst nennt man Rossini auch den letzten Barockkomponisten. Aber mit der Colbran änderte sich auch seine Ästhetik in Richtung weniger stereotyper Rattermaschienen und zugunsten von dunkler Poesie, Seelenängsten, individuellerem Ausdruck, wie die frühromantische Donna del Lago so überzeugend zeigt.

Der gesellschaftliche Mittelpunkt ihrer Zeit und von Rossini in seinem „Viaggio á Reims“ verewigt: Madame de Stael/OBA

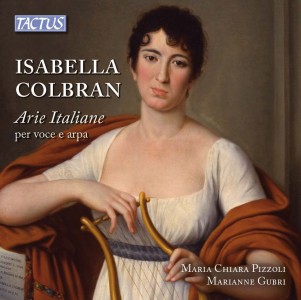

Eine neue CD bei Tactus wirft nun Licht auf einen ganz anderen Aspekt der Isabella Colbran – sie war wie alle Künstler der Epoche hochmusikalisch und ebenso ausgebildet und dazu eine Komponistin von nicht unbeträchtlichen Graden (ähnlich wie die Vorgängerin Malibran und andere Kollegen/-innen): Lieder zur Harfe, ein Klassiker für die Salons des Adels und des Bildungsbürgertums einer Madame de Stael und der Pariser Gesellschaft. Der nachfolgende Artikel von Marianne Gubri im Beiheft zur Tactus-CD nimmt sich dieses Themas (in Englisch, jaja!) an. Bienvenue, Madame Colbran! G. H.

The four books of Canzoncine ou Petits Airs Italiens by Isabella Colbran (1784-1845) were composed between 1805 and 1809, during her youth, before her marriage to Gioacchino Rossini (1822) and the beginning of her career as prima donna of Italian opera. Isabella Colbran was born in Madrid, received her initial musical education from her father, Juan Colbran, violinist in the Capilla Real, and studied singing under the guidance of the celebrated Italian opera singers and castratos Carlo Martinelli and Girolamo Crescentini. She dedicated to the latter one of her song collections, and sang many of his compositions.

After a few concerts in Madrid, she was appointed as court singer by the Queen of Spain, and held this post from 1803 to 1808, as declared in the front page of her first three song collections. In 1804, Isabella and her father went to Paris in quest of success. She sang in the house of Rodolphe Kreuzer, who had founded the publishing house Le Magasin de Musique two years before, together with Cherubini, Mehul, Rode, Isouard and Boiledieu. Le Magasin de Musique subsequently published three of Isabellas collections. She probably referred to the above-named musicians in her dedication to the Queen of Spain, when she mentioned them as promoters of the edition, with an attitude of obsequious humility that was customary at that time (…) It was published by Miles Erard, a publishing house that had been established by the daughters of the famous harp- and piano-maker (one of the two sisters, Celeste, later married Gaspare Spontini).

On 21 November 1806, while she was still travelling between Spain and Italy, she became a member of the Accademia Filarmonica of Bologna, where she performed in 1807: this title was mentioned in the song collections subsequent to that date. In the portrait by an anonymous painter that we present on the cover, (which was donated to the Liceo Musicale of Bologna during that stay of hers, and is now preserved in the Museo della Musica of Bologna), she is depicted as a young woman holding a lyre, which rests on a copy of her first book of songs. On the cover of this book, her new title of academician has been added by the painter, though at the time of the printing of that work the title had not been awarded to her yet: so it is possible to conclude that the portrait was painted in 1807.

Die „Konkurrenz“: Maria Malibran, selber Spanierin, als Desdemona in Rossinis „Otello“/Gemälde von Bouchot/OBA

After her stay in Bologna, where she probably met Gioacchino Rossini, who was then a student and was eight years younger than her, in 1808 Isabella returned to Paris with her father. There she held both private and public concerts; she sang often in aristocratic houses, for the Empress and for ambassadors, but her greatest success was in her public concerts. The press extolled the range of her voice, which included almost three octaves, and its clear, resounding timbre, her mastery in the art of the messa di voce, her expressive, sweet interpretation, her good Italian, and the variety of her repertoire, which was formed of arias by Zingarelli, Portogallo, Nasolini, Mayr, Haydn and her teacher Crescentini.

In 1808 she dedicated her compositions to Louise Marie of Baden (wife of Emperor Alexander I of Russia), and in 1809 to Marie Julie Clary Bonaparte, wife of Joseph Bonaparte, who hired her as a chamber-music singer as soon as he became King of Spain. The last months of the year 1809 marked the beginning of a long, uninterrupted career for Isabella Colbran as an opera singer, first at the Teatro alia Scala of Milan, then at the Teatro Comunale of Bologna, at the Fenice of Venice, in Rome, and eventually, from 1811 onwards, in Naples, where she was consecrated as „Prima cantante assoluta‘ („the first singer by far“) and sang in the operas by her future husband.

La Vestale by Gaspare Spontini was staged in Italian, in the translation by Giovanni Schmidt: Isabella sang in the role of Giulia. The opera was so successful that its performances were repeated until 1816. The aria „O nume tutelary” is included in this CD as an addition to Isabellas compositions, in the handwritten, probably autograph, version preserved in her collection, now housed in the Library of the Conservatoire Royal of Bruxelles. This version is particularly interesting, because, in addition to Spontini’s original part, the singer has written down her own embellishments on a further staff, according to the customary bel canto practice of that period. This sheds light on the virtuosic and dramatic aspect of the performance, and reveals the fact that the performer enjoyed a certain independence of interpretation in relation to the original composition.

The Barcarola Gia la notte s’avvicina has been drawn from a collection of Passatempi musicali o sia raccolta di Ariette e duettini per camera inediti, Romanze francesi nuove, Canzoncine Napolitane e Siciliane, Variazioni pel canto, Piccoli Divertimenti per Pianoforte, Contradanze, Walz, Balli diversi etc. published in 1824 and containing,, besides Isabella Colbrans arietta, pieces by Cottrau, Donizetti, Filed, Leiderdorf, Pacini, Rossini, and Schubert. The title of this collection emphasises the fact that it was meant for amateur performers.

Isabella’s stay in Naples was a very rich, complicated period, not only for her artistic activity, but also for her private life. On 16 March 1822, almost in secret, she married Gioacchino Rossini (by then quite famous) in the Chiesa del Santuario della Vergine del Pilar at Castenaso (a few kilometres away from her father Juan’s villa). The extraordinary rise of Rossini’s career as a composer allowed him to expand into new theatres and new cities, particularly Paris and London; but it also led him to embark on new liaisons, above all that with the courtesan Olympie Pelissier, whom he married when Isabella died at Castenaso, years after she had left the stage and had been abandoned by her husband.

In this recording of pieces composed by Isabella Colbran, we have not included the cantata Pelgiorno natalizio di Giovanni Colbrand,for voice and piano, now preserved at the Conservatory of Bruxelles, because it is incomplete. Other two songs Alma delValma mia and No, che lasciar non posso, now preserved in Madrid at the Biblioteca Nacional de Espana in a manuscript entitled Canzonifate aproposito del Sig.re Gerolamo Crescentini have been ascribed to Isabella Colbran by Sergio Ragni in his book Isabella Colbran, Isabella Rossini, but it is more likely that they were composed by Girolamo Crescentini1 and dedicated to her. The first of these two songs has actually been included in several collections of Crescentini’s arias.

Isabella Colbran’s compositions are typical of the chamber-music repertoire for amateurs: they consist of short, melodious, through-composed arias with two texts: one in Italian, drawn from Metastasio’s poems, the other a free translation into French. The vocal characteristics they require are those of a voice that is seemingly average but includes some unusually high notes for a soprano.

The four song books offer the choice of a harp or piano accompaniment, as customary during that period, particularly in the French repertoire: Marie Antoinette, and after her all the French ladies at court, completed their education by learning to play the harp. Empress Josephine de Beauharnais, for whom Isabella Colbran performed, was the inspirer of the composition of a great number of chamber-music pieces for harp. Since the end of the eighteenth century, the harp was equipped with a single pedal movement that allowed the performer to achieve modulations and chromaticisms. In the first years of the nineteenth century, Sebastien Erard, a well-known Parisian piano maker, began his research for the creation of a harp with a double pedal movement that gave greater freedom to the player: he patented this device in 1811. The new instrument was soon adopted also by professional harpists.

Isabella had the chance to meet two of the greatest harpist/composers of her time: on 16 April 1808 she sang during the same evening in which Charles Bochsa performed in the premiere of his concerto n. 1 op. 15. In August 1827, at Arques, she sang together with Francis Joseph Naderman. Moreover, in February 1811 she sang with a Mrs Rega, Neapolitan amateur harpist.

The accompaniment to these little songs, which is simple but varied and follows the pattern adopted by composers such as Cherubini, Crescentini, Spontini, Isouard, and Boiledieu, with a melodic introduction and a realisation based on chords or arpeggios, can easily be adapted to the harp without any particular changes. Publishers such as Le Magasin de Musique and Miles Erard were doubly interested in offering works for both instruments: the prospect was that the French ladies would be keen both to perform new repertoires and to own instruments often made expressly for them.

Although a newspaper published at the end of the nineteenth century states that Isabella Colbran also played the harp, it is likely that this assertion stemmed from a misinterpretation of the pictures in which she held a lyre in her hands. During that period several paintings portrayed her and other female singers in Empire-style dress and with Apollo’s instrument: it was a clear allusion to the classical antiquity from which the Napoleonic neoclassical style drew inspiration.

Actually, the funerary monument for Isabella’s father – Juan Colbran, who died in 1820 – designed by Gioacchino Rossini and made by the sculptor Adamo Tadolini – shows a cherub who is playing the lyre while Isabella is weeping and looking at her father’s memorial bust. This grave also accommodates the bodies of Rossini’s parents, Anna Guidarini and Giuseppe Rossini, and of Isabella, who died in 1845 in her villa at Castenaso.The monument can still be seen in the Chiostro Maggiore Levante, Arco VI, of the cemetery of the Certosa of Bologna: the recording of this CD has been carried out in the adjoining Chiesa di San Girolamo.

Den Artikel von Marianne Gubri, selber Harfenistin von Rang, entnahmen wir in der englischen Übersetzung dem neuen Album bei Tactus (TC 780302): Isabella Colbran – Arie italiane per voce e (!) arpa, auf der die Autorin die Mezzosopranistin Maria Chiara Pizzoli auf der Harfe begleitet. Die Fußnoten in dem Artikel von Marianne Gubri wurden aus Platzgründen fortgelassen. Redaktion G. H.)

Und dazu noch kurz den Auszug aus Wikipedia: Isabella Colbran (Geburtsname Isabel Colbrandt) (* 2. Februar 1785 in Madrid; † 7. Oktober 1845 in Bologna) war eine Mezzosopranistin und Komponistin. Sie gehörte zu den berühmtesten Sängerinnen ihrer Zeit. Sie begann ihre Karriere am Teatro San Carlo in Neapel, wo sie nicht nur vom Publikum, sondern auch vom König von Neapel bewundert wurde. Mit dem Impresario des Theaters, Domenico Barbaja, hatte Isabella Colbran eine Affäre. Barbaja engagierte Gioachino Rossini, der für Isabella Colbran einige Paraderollen schrieb (unter anderem Elisabetta, Desdemona/Otello und Armida). 1822 heirateten Rossini und Colbran. 1837 trennten sie sich wieder, Rossini hielt sie jedoch immer für eine der besten Interpretinnen seiner Werke. Isabella Colbran schrieb vier Liedersammlungen, die sie der russischen Zarin, ihrem Lehrer Crescenti, der spanischen Königin sowie der Prinzessin Eugenie de Beauharnais widmete.

Auf die interessante Ausgabe aller Lieder von Spontini bei Tactus haben wir bereits hingewiesen/TC 771960.