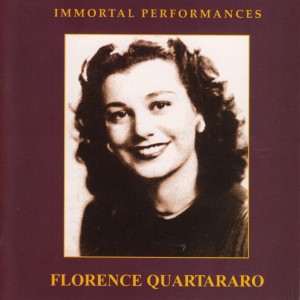

Was gibt es doch immer wieder für Überraschungen, auch auf dem historische Sektor. Da kommt von Immortal Performances eine 3-CD-Box der mir bis dahin absolut unbekannten amerikanischen Sopranistin Florence Quartararo mit seltensten Aufnahmen von 1945 – 1951, die eine ganz erstaunliche Stimme hören lassen: eine Mischung aus Bidu Sayao und Eleanor Steber plus ein starkes Quentchen Ponselle (und dies nur als Hörvorgabe), blond, individuell, eher lyrisch als spinto (auch wenn der renommierte Kritiker Henry Fogel im Booklet-Text mehr das Dramatische in der Stimme preist und betont), flexibel mit einem sehr persönlichen Ausdruck und einer erstaunlichen Modernität im Ausdruck – also gar nicht historisch oder dünn-muffig. Sicher, in den Trovatore-Auszügen merkt man die Grenzen der schönen Stimme, aber im Figaro, in den Standardstücken wie die aus Tosca, Don Giovanni, auch Butterfly hat man eine gültige Sopranstimme und eine interessante Interpretation vor sich. Interessant ist auch das Repertoire der Sängerin, die nur 37 Vorstellungen an der Met der Nachkriegszeit sang (4 Saisons), die aber doch auch glamouröse Auftritt in der Hollywood Bowl bestritt, mit Bing Crosby (dem sie 1945 als Florence Alba vorsang) und Ramon Vinay für RCA Aufnahmen machte und die ein breites Repertoire nicht nur an Oper, sondern auch an Unterhaltungsmusik mehr oder weniger verdächtiger Titel bestritt. Die Ehe mit dem italienischen Bass Italo Tajo beendete ihre kurze Karriere. Auf youtube ist sie mit verschiedenen Aufnahmen zu hören, die aber weitgehend von den Immortal-Performances-Dokumenten „ausgeliehen“ sind.

Spannend für mich sind ihre französischen Aufnahmen der Micaela, der Filles de Cadix (damals sehr populär) oder Thais – für letztere hat sie die ideale Stimme und klingt sehr idiomatisch. Dass dies eine wichtige und auch einmalige Stimme ist, hört man bei den ersten Tönen, und man hört auch, dass sie eine betörend schöne Frau gewesen sein muss, wie die vielen Fotos im üppigen beigefügten Booklet zeigen, die wir hier ebenso nach-„drucken“ wie den nachfolgenden Text daraus von dem Herausgeber und künstlerischen/technischen Chef vom Immortal Performances, Richard Caniel, der Sammlern natürlich kein Unbekannter ist, hat er doch seit vielen Jahren unermüdlich historische Aufnahmen namentlich von der Met, aber auch mit der Jurinac oder Leider in bestem Sound herausgegeben. Ein späterer Artikel auf operalounge.de beschäftigt sich mit seinen neusten Arbeiten eben aus der Met, und ein Tristan aus London mit der Flagstad ist avisiert. Im Folgenden also eine Hommage an Florence Quartararo von Immortal Performances mit Texten und Fotos zu ihren Ehren. Geerd Heinsen

„A surprise is the Vinay-Quartararo Tosca-duet, not so much for Vinay’s fine performance of Cavaradossi’s music, but for the really lovely voice of the soprano, who, after only a few seasons at the Met, disappeared from the scene.“ (Harold Rosenthal, Editor Opera, February 1970). Just about every opera lover I’ve ever met who has heard the few 78 rpm recordings Florence Quartararo made for RCA Victor, or who heard her unusually expressive, brilliantly sung performance of the Countess in Nozze at the Met or Desdemona in Otello, asks „Whatever happened to her?“ Small wonder that after 49 years such interest still remains. Quartararo was a remarkable artist with a memorable voice and an unusual feel for the text and drama of what she sang, and yet she simply vanished just as her career had gained great momentum. She made her debut as Micaela. This was the role of which Howard Taubman, the music critic of the New York Times wrote: „The young lady sang with astonishing assurance. She may be the find of the season. She has a voice of size, range, and true lyric quality. It is produced with a smoothness and accuracy that makes you wonder how it happened that this voice has been so well placed. One gathered that she had not had much formal vocal schooling. Perhaps it is so. As for Micaela’s music, Miss Quartararo sang it with affecting simplicity. It is deceptive music, it looks easy, and it does not overpower as does the music of Carmen, but it takes sensitivity and quality as a singer. Miss Quartararo, who is also good to look at, seems to have what it takes.“

Quartararo was the protegee of Bruno Walter, the soprano Toscanini telephoned personally to congratulate for her Desdemona and to request she audition this role for him for his forthcoming broadcast; the soprano Fritz Busch admired in Mozart, that Walter conducted as Pamina in his Magic Flute. This is the same soprano whom I saw in 1946 when I was 14. She was my first Micaela at the Met and the one whose 78 rpm disc of the duet from that opera I prized as a boy. Little did I imagine in the intervening years that I would spend three warmly rewarding evenings with her 36 years later.

Our three meetings introduced me to a rare and savorable personality. Like a number of opera singers, Florence Quartararo has a presence larger than ordinary people – a quality which makes it possible for them to fill the stage and huge auditorium at the Met or San Francisco Opera not only with their voice but by a substance, a contained energy which makes them stand out. She was a still beautiful woman in 1982, warm, personable, expressive. Her charm had none of the professional patina which those who have had considerable success and press coverage soon acquire, rather it was natural in its tone and color, hued with a certain Italianate earthiness, touched at first with a hint of wariness while she listened for whatever was the spirit behind what I said.

On our third meeting, which occurred at her lovely home, we turned to the subject of her career and subsequent history. To tune me to the subject I asked her to play one of her recordings. She chose La mamma morta (Andrea Chenier), a Victor recording I had not previously heard. „What did you think of it?“ she asked me when it had ended. I tried not to frown. „It is beautiful in its way, but it doesn’t open up (at “Ne‘ miei occhi e il tuo cielo”).“ „Exactly!“ she said. „That’s just what was wrong with it. I was so inexperienced and Morel (the conductor) couldn’t see its expansion. I didn’t argue,“ she concluded sadly.

At this point, the evening changed; our relationship had suddenly deepened. “La mamma morta” wasn’t asked about as a test but it was one nonetheless, as any true artist wants to avoid sycophancy, perhaps because nothing real can be exchanged when that bias is present. „Now, I’ll play something else,“ and we heard “Care selve”, which to my ears was thrilling and I said so.

Soon we turned to her career and the reason why it ended when it had begun to soar. Born of Italian parents in the Bay area, she was, from the beginning, present in an opera-loving milieu. Merola, head of the San Francisco Opera and its chief conductor, was present at her baptism. In her childhood she sang as far back as she could remember. Her idol was Muzio whom she saw in Traviata. She went to the San Francisco Opera as a standee whenever Muzio sang. She exclaimed, „What emotional capacity she had, what sensitivity, the variety of her characterization of Violetta! Nothing false, excessive, everything harnessed and yet how it poured out, this music in her, to the public. I also loved to hear Ponselle (what a dramatic instinct), Rethberg who had a glorious voice and Mafalda Favero who had an outstanding stage presence. I couldn’t get enough of Gigli, Schipa, Borgioli and Martinelli, all of whom sang at the San Francisco Opera.‘

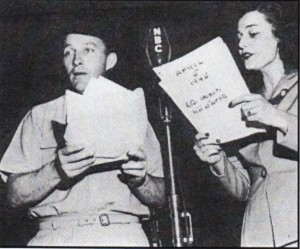

The operatic milieu included her father, a medical doctor (ophthalmologist) who played piano and sang. Her mother’s brother was wild about opera and a close friend of Merola. „Music was always around me.“ Florence began her vocal studies with Elisabeth Wells in San Francisco and then continued with Pietro Cimini in Los Angeles in 1944. „After I graduated from college I went to work for the Navy department and through friends I met Bing Crosby. He auditioned me and put me on his Kraft Music Hall (as Florence Alba, her original stage name). I did four performances. I then had an audition with Stokowski for the Hollywood Bowl concerts he was conducting but nothing happened. Then, one day, I received a telephone call asking me to take the place of Helen Traubel in a concert she was to sing of Wagner arias conducted by Otto Klemperer. He had to change everything to accommodate the lyric soprano arias I could sing.

„Then my life really changed. In the audience was Earle Lewis, an important man at the Met. He came to me and said T want to arrange for you to sing for Bruno Walter.‘ And so we went to see the great conductor at the Beverly Hills Hotel; he had a salon there. He played the piano himself, no one else was present. I shall never forget this sweet, lovely man. We began with Depuis le jour. I blanked out after the first phrase I was so frightened, but he was so incredibly kind he helped me over this kind of collapse. We did Mozart for an hour. Then he said he would write Edward Johnson, the General Manager of the Met. He didn’t say what he would write about me and I didn’t ask. This was in the early fall of 1945.

Florence Quartararo: „Figaro“ mit Bidu Sayao und Herta Glaz – eines der seltenen Fotos der an der Met unverzichtbaren Comprimaria in jugendlichen Mezzopartien wie Cherubino oder Sièbel/Foto Immortal Performances

„Eventually my audition at the Met came about. Cimini said, ‚Just go out and sing. Don’t try to hear yourself.‘ The assistant conductor said before I went on, ‚Just pray to God and sing the best you can. You can’t pitch your voice because you don’t know the house.‘ What a thrill to be on the Metropolitan Opera stage — the greatest of our theaters! I sang from Boheme, then Dove sono and Sempre libera. No one said a word. I had to leave the stage in silence and go home and wonder. Then Mr. Johnson himself telephoned me and said he wanted to hear me in an NBC studio. After that I won their Caruso Award which took care of my study and a Metropolitan Opera contract.

„I was assigned the roles of Micaela, Elvira, Desdemona, Countess in Nozze, Pamina, a Walkure and Parsifal maiden; I was to attend every rehearsal possible on the stage or roof and I was also to study dance and makeup. I was told, ‚Watch everything. If you get to sing, you may not have a rehearsal“. „As it turned out I made my debut as Micaela in a cast which included Vinay, Stevens and Merrill. Vinay’s Don Jose was very vital, very virile. He had marvelous temperament and was capable of very exciting singing. He was an important vocal personality This made up for what he lacked in vocal ease.“

I saw her Micaela at a student performance in which the cast was the same, except Djanel took over for Stevens. I was entranced by Quartararo, who I thought movie-star beautiful, with the added virtue of singing with such shining loveliness and much dramatic intensity. The critics who „happened“ to show up for Quartararo’s debut likely came because they’d been alerted that an unusual voice was to be unveiled.

Robert Bagar of the New York Word Telegram wrote: „A lovely voice, very good looking and a first class musician.“ Of her debut, Quartararo told me: „I was petrified. I don’t think I knew where I was until the third act, I was so scared. One side of me prayed, Dear God, open the stage and let me disappear, but still, whether it was the ham in me, I couldn’t wait to get out there. It was all somehow like a storybook.“

Quartararo went on to sing 37 performances at the Met in nine roles: Elvira in Don Giovanni; Violetta in Traviata; Micaela in Carmen; Flower maiden in Parsifal; Lauretta in Gianni Schicchi; Contessa in Nozze; Nedda in Pagliacci; Pamina in The Magic Flute with Bruno Walter conducting and Desdemona. Of this last, her chance came when Stella Roman fell ill and on a few hours notice, without rehearsal, she took over the role, singing with Torsten Ralf and Leonard Warren.

Taubman of the New York Times was again enchanted with her singing, writing: „Her voice is perfectly suited for Desdemona and she used it last night with a sure instinct for the molding of the musical phrase. She had at her command a finely controlled range of tone and in the last act her singing of the Willow Song and Ave Maria made you forget the soprano on the operatic stage and left you only with the heartbreak of the poor bewildered Desdemona.“

Her experience singing Desdemona was greatly enlarged when she received a telephone call in which an aged voice, speaking in Italian, said he was Toscanini. „As he went on to say, T heard that you sang very well last night/ I interrupted, believing it was all a joke or hoax played by some friends. ‚No, no,‘ I told him. ‚I don’t believe you.‘ ‚Si, si, signorina“, he said, ’sono Toscanini“ He kept it up, so serious, that I finally realized it was actually the great Maestro. I was speechless. He wanted me to audition for him for Desdemona. Toscanini’s helper, he prepared me, Toscanini played the piano. We went through Addio del passato and music from Otello and he taught me more in a half hour than I had learned in a few years. It was overwhelming to be with so great a genius, it was such a privilege. When I went to his rehearsals, I saw why he was the greatest Maestro. Toscanini and Bruno Walter – they were the highest achievement in musical genius. Toscanini especially drew so much out of everyone. He wanted me for his opera broadcast of Otello but the Met wouldn’t release me for the numerous rehearsals Toscanini required [as they wouldn’t release Albanese for his Falstaff.“

Quartararo, for all the brevity of her career, had actually sung under many fine conductors: Klemperer, Ormandy, Busch and in particular Bruno Walter. She recalls his encouragement when she was to sing Pamina in The Magic Flute: „I have faith in you: We’ve worked on it. Just look at me and I’ll support you, help you in every way I can.“ She says: „I felt as if I had arms around me holding me up.“ Of her Met colleagues, she much admired Bidu Sayao, saying: „She was exquisite – beautiful to look at – the total artist, nothing missing; her clothes, her walk, her tone; her voice, small, reached to every part of that huge auditorium – a marvelous, masterful musician. Rise Stevens was another one I admired, and she was such a great help to me, truly sincere, never treating me like a youngster, helping me with my makeup.“ Later, when she sang Nozze and Don Giovanni with Pinza, she said of the great basso: „What a thrill to hear him sing, “Deh vieni alia finestra”. It’s true he pinched ladies like a naughty boy but he was a very serious artist. I use that word ‚artist‘ not too often. Many singers are not complete. They give no true emphasis to the words — like a painting without color – but an artist gives you an entire experience. Don’t pick on one phrase, one passage, like Vinay’s Esultante – listen to what he did with the rest of the role! Tremendous!“

Of her Mozart, a composer she adores, Quartararo has garnered praise from many quarters. Claudia Cassidy, the Chicago music critic who championed Callas when she first came to Chicago, wrote (after hearing Quartararo sing “Porgi amor”): „Her singing staked a claim on one’s undivided attention. She sang superbly, with serenity and simplicity and security that comes from a wealth of resources in reserve. If that girl doesn’t make opera sit up and take notice, I shall desist consulting my crystal ball.“

Pinza said of her in Mozart, „She suffers violently to go on and she goes out and kills everyone (esse mazze tutti)“ When she sang in Nozze di Figaro at the San Francisco Opera with Pinza and Baccaloni, the opera critics went wild: „Her voice was full, warm and radiantly clear. She sang with much dramatic emphasis with an excellent sense of Mozartean style. She didn’t quite realize how wonderful her voice is. Few have such color, roundness and intensity, full of warmth, softness, pathos and grief.“

All the while Quartararo’s mounting success didn’t change her sense of her limitations. Nor did adulation give her an enlarged sense of status. „I was reared that way – what I had was a gift from God for which I had to become worthy. I needed to develop further restraint. The more I sang, the more I began to know what I must do – how to spare myself, how to open myself. I would read scores at night in bed, going over the words, trying to sink into their meaning, trying to avoid banalities. I needed to learn how to stand still. All this takes enormous experience. By your thirties you might begin to bring heart, movement and dramatic abilities together to be whole with your voice. Had I remained in my career, I would have paced myself differently. Youth wants to give, give. Maturity knows restraint, holds back so that the climax has shape. I had to put holds on physical abandon but not on spiritual abandonment which is totally necessary.“

Here, then, was a soprano with a glorious career opening before her in a shining avenue of opportunities and yet, for all the roles she finally got a chance to sing – Thais with Martial Singher, Traviata (when Taubman compared her favorably to Rosa Ponselle), Faust with Kullman and Pinza when the Metropolitan Opera was on tour, it was not to be. She made some Victor records: the Micaela duet with Vinay and the Tosca Act I duet with the same tenor. Here one hears what a Tosca she might have given us.

She told me that our previous meeting inadvertently touched the subject of „what could have been“ and struck a painful place in her. But its wound, though deep, was covered over with a lifetime of experience which ran in a different direction. What happened? She met Italo Tajo at the Met when appearing as Lauretta in Gianni Schicchi in which he sang the title role. Some time afterward, she married him. „He believed one singer in the family is enough.“ He said this when she gave birth to a lovely daughter. „And this birth gave me the courage to break from my career.“ Her recollection of her involvement in the years of her daughter’s infancy suffused her tone with an extra warmth: „The biggest thrill of my life was when I had my child, something totally yours. What greater fulfillment could there be than a child? It deepened me.“ Then, after a long ruminative silence, the other Florence, the singer that lives in a world apart, a person with an altered evolution, life and prospect, spoke: „There was, perhaps, one other experience that gave me something of this same thing – standing on the Met stage, giving oneself and the audience receiving it. There was a tremendous sense of achievement. You could tell by the conditions, the atmosphere, if you were doing right. You feel it in the orchestra. If the musicians stand up and applaud at the act end, you know it was good. This meant so much, the professionals‘ response. You looked for this and when it and the audience came together, that you have given them these emotions, not just experienced them yourself, what fulfillment!

„If ever I have a moment of regret for not continuing on the stage, it is the feeling of something unfinished, like something that wanted to complete itself. I don’t know. It was like a great book, the end of which I had left unread. But then, you know, one’s career has a build, a momentum. By the time my child was old enough for me to consider other possibilities, the momentum had been lost. Still, it may have been brief but it was wonderfully fulfilling, rewarding in ways for which I have no language.“ Florence again referred to this subject in a letter she sent to me in which she said that our talk had „… brought me back to a life lived so long ago and memories exciting and fulfilling but at the same time painful to some degree. „However, don’t most worthwhile experiences follow this bittersweet pattern of ups and downs, with tears and joys all mixed together and nearly impossible to distinguish one from the other?“

Florence had been a bit resistant at our first meeting to re-enter the past she had managed to seal away. However, my enthusiasm and regard for her singing, together with our underlying affinities, led her back at last through the more than thirty years which had passed to a period which she not only cherished but which, at some level, remained ageless.

Florence had been a bit resistant at our first meeting to re-enter the past she had managed to seal away. However, my enthusiasm and regard for her singing, together with our underlying affinities, led her back at last through the more than thirty years which had passed to a period which she not only cherished but which, at some level, remained ageless.

Looking back at her past had brought up the private recordings she had in her possession, as well as the memory of some discs she once had but which were lost through loan to a person who promised to transcribe them onto tape but had instead vanished. I promised to hunt down acetates of the performances which she did not have (and which two confreres managed, with extreme resourcefulness, to find). I also hoped I could find the portion of the recording of the complete Pagliacci broadcast in which she sang that was missing in her acetates. I promised, as well, to put some restoration work in on them so that, eventually, opera lovers could hear for themselves what it was in her singing that had the music critics praising her so highly.

Alas, a thousand interventions held us up, especially the development of our Music Society, the Metropolitan holdings and the Toscanini Broadcast Legacy, so that I arrive at this offering of her recordings not as a bouquet of promises finally kept but, sadly enough, as a memorial. Florence Quartararo passed away in June 1994 at the age of 72. Yet, in some important way, she lives among us through what it was she most prized besides her family – her art. These recordings, largely derived from her personal collection, are a precious part of our mutual legacy and we are grateful to be enabled to share it with you.

As for Florence, wherever she is now, the broken melodic thread of musical continuity has been rewoven, the unfulfilled promise kept, all in that special heaven where every word and action is music. She has gone at last to where converge all the great singers and musicians of her youth, to where she can sing at last for Toscanini, to where she can read at last the final pages in the book of her life left so long unread. Surely there she will find the unexpected and divine happiness she has truly earned. My experience with Florence Quartararo was the main subject of a radio documentary made about my work by the CBC some years ago.

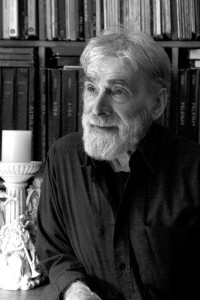

Florence Quartararo: Opernliebhaber, Restaurator und Sammler – Richard Caniell/Foto Immortal Performances

This was broadcast nationally two times in 1999 and two times in 2000, the latter rebroadcasts due to the fact that the documentary won the World Gold Prize for Best Radio Documentary (Classical) at the International Festival of Radio and Television held in New York in June of 2000.1 don’t doubt Quartararo’s singing, heard during my interview, contributed chiefly to the winning of the award. (…) Richard Caniell

Florence Quartararo: Opera Arias 1947 – 1950 (Massenet, Cilea, Catalani, Verdi, Del Regio, Leoncavallo, Mozart, Charpentier, Bizet, Puccini, Oscar Straus, Rodgers; diverse Aufnahmeorte und -Quellen); 3 CD Immortal Performances IPCD 1030-3