.

Zu den spannendsten Erscheinungen unter den Komponisten der Revolutionszeit (davor und danach einschließlich) gehört in Frankreich Étienne-Nicolas Méhul, der die Schrecken der Commune überlebte, zu Glanz unter Napoleon aufstieg, aber auch in der Nachrevolutionszeit sich einen bedeutenden Namen machte. Er lebt im Erbe Glucks und nimmt in seinen Sinfonien und Opern in vielem Beethoven und die kommende Klassik voraus . Er hat diesen drängenden Gluck-Drive, diese spannende Behandlung der orchesterbegleiteten Rezitative und den Atem für großangelegte Solo- und Ensembleszenen. Ein Blick zu Amazon oder jpc zeigt, dass es doch reichlich Méhul auf dem Markt gibt, seine Opern, an erster Stelle Stratonice (unter Christie/Erato), sowie Joseph (verschiedene Aufnahmen, namentlich die aus Compiegne/cdm), L´irato und anderes mehr, vor allem auch die Sinfonien und reichlich Kammermusik.

.Aber nur Stratonice ist diesem Adrien an Nachdruck und Würde gewachsen, Joseph bleibt in anbiedernder Bibelnähe stecken und kündigt ein neues Genre an, das der pietätvoll gedämpften Bürgerlichkeit eines Benda oder auch Cherubini in dessen kleineren Kompositionen wie Julie ou le pot des fleurs, L’hôtellerie portugaise und vor allem Les deux journées – Werke, die eine andere Ästhetik vorbereiten. Vielleicht ist dies auch der Ort, an dem man auf weiteres von Méhul hinweisen sollte, das Sammler natürlich haben: einen Horatius mit Orliac und Massard gab es beim französischen Rundfunk 196-, Uthal kursierte auf rabenschwarzen Scheiben in einem abenteuerlichen und auch abenteuerlich zusammengebastelten Live-Mitschnitt aus London von 1972 unter Stanford Robinson bei UORC (gekoppelt mit einem dto. Irato) und nun im Konzert 2015 in Paris (mit hoher Wahrscheinlichkeit einer CD-Dokumentation bei Ediciones Singolares), verschiedene Aufführungen vom L´irato kommen aus Tours 1985 und Bonn 2005, vom Joseph gibt es sogar ein Dokument aus Amiens mit Vanzo und Massis 1989.

.

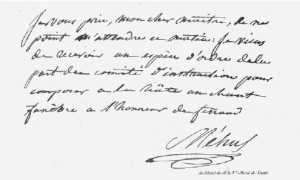

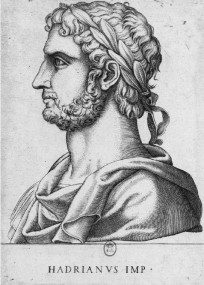

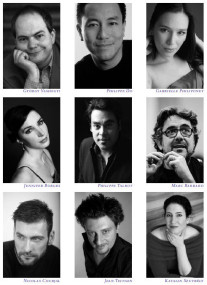

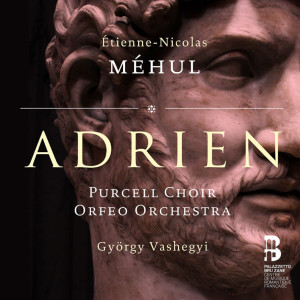

Vom Palazetto Bru Zane gab es (dem Vernehmen nach nur als mp3- und wma-download bei quobuz/Seite nicht mehr verfügbar!) die Neu- und Erstaufnahme des Adrien, die Geschichte vom kriegerischen, aber auch großmütigen Kaiser Hadrian, der seine Feinde begnadigt und ihnen die Freiheit schenkt. Dies 1799 mit deutlichem Hinweis auf Gnade und Großzügigkeit angesichts der Grauen der Revolution, auch in Hinsicht auf Napoleon, ein gütiger Kaiser zu sein. György Vashegyi leitet eine Einspielung von 2012 aus Budapest (die gabs sogar als optischen stream) mit einem hochprofilierten Cast, angeführt von Philippe Do in der Titelrolle, weiters singen Gabrielle Philiponet, der erfahrene Marc Barrad, Jennifer Borghi, Philippe Talbot und weitere Solisten, die schon auf anderen Aufnahmen des Palazetto Bru Zane, der im Rahmen seines Sponsorentums um die Wiedererweckung der Romantischen franzözischen Oper auch diese Ausgabe unterstützte. Nach einer kurzen Einleitung mit einem informativen Text von Wikipedia folgt hier der hochinteressante Aufsatz von Alexandre Dratwicki (in Englisch, sorry), dem Musikwissenschaftler und „Drahtzieher“ der Reihe beim Palazetto Bru Zane, dem man nicht genug Dank sagen kann. G. H.

.

.

Étienne-Nicolas Méhul begann seine musikalische Ausbildung als Organist, und zwar im Franziskanerkloster seines Heimatortes. Später studierte er bei dem Organisten Wilhelm Hanser und wurde 1778 dessen Assistent oder Hilfsorganist an der Klosterkirche der Benediktiner von Lavaldieu in den Ardennen. Im Jahr 1779 übersiedelte er nach Paris, wo er bei dem Straßburger Komponisten und Cembalisten Jean Frédéric Edelmann Kompositionsunterricht nahm. Möglicherweise verdiente er seinen Lebensunterhalt als Organist, wofür es aber bisher keine Beweise gibt. In den 1780er Jahren arbeitete er als Lehrer und veröffentlichte in dieser Zeit zwei Bände mit Klaviersonaten. Der zweite Band war mit einer sogenannten „überlegten“ Violinstimme erschienen, die die Thematik im Klavier verdoppelt. Neben François-Joseph Gossec galt er als der Komponist der Französischen Revolution. Sein Chant national du 14 Juillet 1800, der von Napoleon nach der Schlacht von Marengo bestellt worden war, bekam fast den Rang einer Nationalhymne, und 1794 entstand seine Revolutionsoper Horatius Coclès. 1795 wurde er Inspektor des Conservatoire und Mitglied der Académie des beaux-arts. Méhul wurde vor allem durch seine mehr als vierzig Opern bekannt, von denen Joseph in Ägypten auch gegenwärtig noch aufgeführt wird; Carl Maria von Weber leitete eine Aufführung des Werkes 1817 anlässlich der Gründung der deutschen Hofoper in Dresden. Die bekannteste Melodie aus dieser Oper, die Romanze des Joseph A peine au sortir de l’enfance (dt. Ich war ein Jüngling noch an Jahren) wurde fälschlich als Vorlage für das Horst-Wessel-Lied ausgegeben, dieses geht jedoch vermutlich auf das deutsche Bänkellied Ich lebte einst im deutschen Vaterlande zurück. Neben den Opern komponierte Méhul sechs große Klaviersonaten, drei Ballette, sechs Sinfonien, Bühnenmusiken und Messen. Er hat sich – neben seinem Zeitgenossen und Rivalen Jean-François Lesueur – um die Erweiterung der Stoffe in der Oper sehr verdient gemacht. Auf ihn gehen einige kühne Neuerungen in der Orchestrierung zurück, und Méhul gilt als Pionier in der Verwendung von Leitmotiven. Méhuls Meisterschaft im Umgang mit sinfonischen Formen und rein orchestralen Werken kommt bereits in den Ouvertüren zu seinen Opern zum Ausdruck. Aus Ludwig van Beethovens Briefen ist zu ersehen, dass er den Kompositionen Méhuls großes Interesse entgegengebracht hat; der Einfluss des Franzosen auf seine Oper Fidelio ist unverkennbar. Wikipedia

.

Und nun der Artikel von Alexandre Dratwicki in der Beilage zur Download-Ausgabe: Étienne-Nicolas Méhul: Adrien (1791) “Adrien, another composition of the same time, was in every wayworthy of Méhul’s creative power, with a multitude of new effects,admirable choruses and a recitative that was in no way inferiorto Gluck’s; but by some sort of ill fate, the various successive governments proscribed the work every time it was revived.” (Fétis, Biographie universelle des musiciens.)

Born in Givet (Ardennes), Étienne-Nicolas Méhul received the first rudiments of his musical education from the German organist Wilhelm Hanser. Having arrived in Paris in 1779 with a letter of recommendation to Gluck, he continued his training with the Alsatian harpsichordist and composer Jean-Frédéric Edelmann, who most likely introduced him to the music of Mozart and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. During that time his first two sets of keyboard sonatas were published (1781). By 1789 Méhul had written his first opera, Cora, for the Académie Royale de Musique (the Paris Opéra), but after rehearsals were abandoned (the Opéra was going through financial difficulties at the time) he turned to the opéra comique genre at the Théâtre Favart, where his most important stage works were to be given.

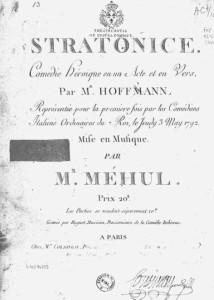

The first of them, Euphrosine (1790), was a new kind of opéra comique marked by the severe heroic style – Méhul referred to the latter as ‘musique de fer’, music of iron – and perfectly in keeping with the expectations of audiences in those Revolutionary times. Stratonice (1792), Mélidore et Phrosine (1794) and Ariodant (1799) all broke out of the narrow confines of the old comédie mêlée d’ariettes (a form of French opéra comique consisting of a spoken comedy interspersed with short arias, which had developed in the mid-eighteenth century) and made opéra comique into the crucible from which the French Romantic opera was to emerge.

Méhul’s quest for ever-greater dramatic expressivity led him to experiment with orchestration: in Uthal, for instance, an Ossianic opera written under the Empire (1806), he replaced the violins in the orchestra with violas for a darker sound. Between 1808 and 1810 he composed his five symphonies. But it was his biblical opera Joseph that was to ensure his fame in Europe in the nineteenth century. Méhul, like the painter Jacques-Louis David, kept pace in his style with the many political upheavals of that period in France. Under the Restoration he composed La Journée aux aventures (1816), recalling in its style and plot the opéra comique of the Ancien-Régime. Méhul died in 1817 of tuberculosis.

In its revised version (recorded here), Adrien begins with a grand overture borrowed from an earlier one-act opera, Horatius Coclès (1794) that is nevertheless very appropriate to its subject; indeed, audiences of the time recognised in it now the solemnity of the emperor’s triumph, now the sighs and tears of his captive, Princess Émirène. The classical structure of the piece naturally opposed two contrasting motifs, easily identifiable as contrary emotions that were relevant to both works. The beginning of the opera contains long passages of mostly ‘dry’ recitative (i. e. with only a simple chordal accompaniment), which the modern listener may find somewhat disconcerting. Composers of that time were actively seeking new ways of modernising the declamation in operatic works, for indeed many critics and also some operagoers strongly objected to a musical style that made shouting obligatory for singers to be heard above the orchestra. Clearly Méhul chose to solve that problem by creating a freer vocal line, less subordinate to the instruments. Furthermore, dry recitative permitted greater freedom of expression, enabling the singers to lend more subtlety to the words of Adrien, Cosroès and Sabine, and bring out the underlying meaning by the use of pauses and however much rubato they deemed necessary; it also facilitated the expression of irony.

Spoken texts predominate in Act I, where they are used to establish the dramatic situation; but after that, the proportion of spoken and sung texts is reversed, with arias and duos providing a finer psychological perception of the characters. In Act I, there are only two sung episodes: a duo for Pharnaspe and Cosroès near the beginning and another one for Émirène and Adrien at the end. The dramatic progression of the latter results in a finale d’acte, a finale to the act, that looks forward to those of Meyerbeer, fifty years hence! There is no orchestral conclusion to encourage applause and the heated conversation between the emperor and his captive is interrupted by a chorus of terrified Romans as the Parthians attack the city. In the ensuing battle, the Parthians are put to flight and the people acclaim Adrien, who has captured Pharnaspe. This scene, superimposing the contrary affects of five soloists and three choruses (chorus of priests and vestals; chorus of Roman soldiers, alternating, then simultaneous with the chorus of Parthians), attains a maximum volume that was unbelievable at that time, and the composer even indulges in the luxury of an amazing symphonic episode.

There is another captivating orchestral piece in the work, apart from the overture. It accompanies the scene in pantomime in which the Parthian soldiers slay their adversaries and strip them of their weapons and clothing in order to disguise themselves as Romans. This purely musical episode – much longer than one might have expected – reflects the use at that time of the pantomime and gesture, both realistic and experimental, that had been developed in Paris since the 1780s within the context of the modern ballet, championed by Noverre and later Gardel. While dance played an important part in the divertissements of the tragédie lyrique, it was rare for the choreography in a work to be represented only by a pantomime scene. Concerning the first version of Adrien, it is difficult to ascertain whether or not there were ballets at the end of the various scenes in celebration of Adrien’s triumph, but it is highly likely that the choruses at the end of Acts I and III were danced as well as sung. Furthermore, the marches that occur at several points in the work must have provided an opportunity for processions or spectacular theatrical actions. Why then did Fétis (born in 1784 and writing many years after the event) explain the work’s short run as follows: ‘While [Méhul’s]Ariodant was being performed at the Opéra-Comique, the administration of the Paris Opéra finally obtained permission from the Directory to stage Adrien, a fine composition, severe in style, that was praised by the critics but which, devoid of spectacular qualities and dancing, was unable to hold the stage for long’? Perhaps the real explanation for the opera’s only brief success was simply that too much time had elapsed between the work’s composition and its performance: what had been modern in 1791 was no longer so, despite the changes the composer had made, in 1799, just before the dawn of the new century of Romanticism. (Übersetzung Mary Pardoe)

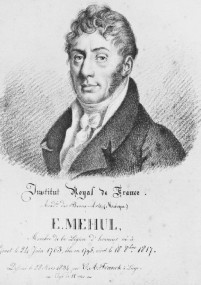

Den Artikel von Alexandre Dratwicki entnahmen wir der Beilage der Download-Aufnahme bei www.quobuz.com, die inzwischen nicht mehr verfügbar ist und die im Juni in 2012 in Budapest unter György Vashegyi mit dem Purcell Choir und dem Orfeo Orchestra eingespielt wurde. Zu den Solisten zählen Philippe Do/Adrien, Gabrielle Philiponet/èmiréne, Marc Barrad/Cosroés, Jennifer Borghi/Sabine und weitere rein Frankophone: Fotos Palazetto Bru Zane/Private Collection. Abbildung oben: Méhul in 1799; portrait by Antoine Gros/ Wikipedia

Den Artikel von Alexandre Dratwicki entnahmen wir der Beilage der Download-Aufnahme bei www.quobuz.com, die inzwischen nicht mehr verfügbar ist und die im Juni in 2012 in Budapest unter György Vashegyi mit dem Purcell Choir und dem Orfeo Orchestra eingespielt wurde. Zu den Solisten zählen Philippe Do/Adrien, Gabrielle Philiponet/èmiréne, Marc Barrad/Cosroés, Jennifer Borghi/Sabine und weitere rein Frankophone: Fotos Palazetto Bru Zane/Private Collection. Abbildung oben: Méhul in 1799; portrait by Antoine Gros/ Wikipedia

.

.

Eine vollständige Auflistung der bisherigen Beiträge findet sich auf dieser Serie hier.