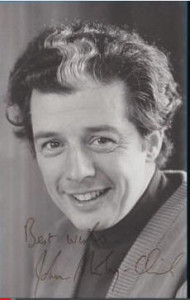

Der bedeutende englische Bass John Shirley-Quirk (geboren am August 28, 1931 in Liverpool, England, gestorben am 7. April 2014 in Bath): Mit ihm geht wirklich eine Ära besten englischen und britischen Nachkriegs-Gesangs zu Ende, denn seine ebenso sonore wie vielfältig einsetzbare und sehr indivuell timbrierte Stimme ist auf vielen Einspielungen von Händel bis Britten und zeitgenössischer britischer Vokallitteratur zu hören – kaum ein anderer englischer Bass ist derart viel und häufig vertreten. Ich erinnere mich an seine Auftritte mit und ohne John Barbirolli in der Berliner Philharmonie, und in England wäre ein Messiah oder eine Missa Solemnis ohne ihn für viele Jahre nicht möglich gewesen. Er hat mit so gut wie allen bedeutenden Dirigenten und Orchestern gearbeitet. Wie seine Kollegen Norma Proctor oder Alexander Young gehörte er zum Besten, das die Insel zu bieten hatte, verfügte über eine wunderbare, warme, stets etwas nasal geführte, herrliche Stimme, zeichnete sich durch exemplarische Diktion aus und war ein Felsen britischen Bass-Gesangs. Man bedenkt bei dieser Todesnachricht, wie schnell die Zeit auch einem selber davon rennt, denn John Shirley-Quirk gehört auch für mich zu den Grundfesten meines eigenen Musiklebens – was für ein großartiger Sänger war er doch. G. H.

Statt eines Nachrufes: John Shirley-Quirk im Gespräch: Helen Pearse sprach mit dem Bassisten im vergangenen Juni (2013) anlässlich seiner Masterclass in Bath und vermittelt ein bewegendes Dokument eines lebenserfahrenen und lebensfrohen Sängers, der nun im April 2014 in seiner Wahlheimat Bath verstarb. Wir haben den Wortlaut unverändert gelassen, daher das vielleicht verwirrende Präsens im Vorspann. Unsere Kollegen von der website fromfestival.uk (http://www.fromefestival.co.uk/the-john-shirley-quirk-interview/) und die Autorin und Journalistin Helen Pearse waren so liebenswürdig, uns den Text zu überlassen, wofür wir uns außerordentlich bedanken! G. H.

How to compress a life time of musical memories and experience into an hour-long conversation? Helen Pearse meets John Shirley-Quirk, one third of an alchemical musical partnership with Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears, that propelled all three onto the world stage. This summer sees the return to a UK audience of one of the twentieth century’s pre-eminient bass baritone voices. John Shirley-Quirk will lead a public masterclass at Cooper Hall as part of the Britten Centenary celebrations in which he passes on his ‘Britten torch’ to six professional singers.

John Shirley-Quirk is sitting calmly on a sofa beside me in an elegant living room, his watchful green eyes and halo of silver-grey hair my focus as we begin our conversation. He is a tall, slender man with a fierce intelligence. I frame my questions with care. Aware that he has returned to the UK after a long absence – he retired just a couple of years ago from a twenty year tenure at the presitgious Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore – I decide to take him back to the very beginning, to his childhood in Liverpool, where his musical life began in the tumult of war.

“My parent were living in Wallesley, across the Mersey from Liverpool, at the time of my birth at the tail-end of August 1931. My mother was the proverbial housewife, my father a civil servant who worked in the the passport office. So, no. I had no ‘musical’ beginnings,” he tells me, “at the age of nine though, in 1940 – just a year after war had been declared – I joined a local church choir in Liverpool, and that was it. My voice changed over the years – from soprano to alto and finally to bass baritone – but I would have been singing wherever it ‘landed’. I think I’d got the singing bug by then. I didn’t realise I was going to have a remarkable career in music until I was forty…”

“During the war I was evacuated to North Wales, it was completely unsafe in the middle of Liverpool. Between the ages of nine and ten, after the war was declared, I lost a year of my life. It took a lot of making up. Schools everywhere were closed. Everyone was expecting an instantaneous invasion. All schools were turned into hospitals. Tiny schools were hastily convened in people’s houses with tiny classes. At the age of ten and a half I won a science scholarship to Liverpool Grammar School. And that’s where my first serious music lessons took place. My first music teacher asked me to sing a solo at the school’s Speech Day – the first time I sang in public – I remember it was ‘Flocks are Courting’ by Buononcini. Then there was Dr Marshall. Around that time, more or less by accident, I had taken up the violin. My parents could just afford the lessons at one shilling per five minutes. They used to last much longer, of course. We bought a low-grade violin for £3 too, I think…” By the age of thirteen I had won a music scholarship which allowed me to have free music theory and violin lessons which took place as evening classes all over Liverpool. I was still singing in the choir. My piano career was over before it started though, due to an injured finger”. At this point he holds up a digit that bends alarmingly at right angles. “Fine for holding a violin bow, but the end of my piano career,” he smiles, ruefully. “By the age of seventeen I was made assistant ‘Choir Master’, teaching lots of 17th century contrapuntal church music. This meant that I had to teach myself the piano. I’m a very bad pianist,” he confesses. Shirley-Quirk then took up a place at Liverpool University to read chemistry, “I was very good at chemistry at school – it was great fun. I got quite good at it.” But the musical thread was never lost, “at university I took part in the chorus and the orchestra and small chorus – where I learned a lot of music. I’ve enjoyed music all my life. It’s always been an absolute thrill and delight – even though it is a hugely stressful profession.”

Bei der Aufnahme von Brittens Kantate „The fiery furnace“ 1957: Roger Brenner, John Shirley-Quirk und Robert Tear/Tony Palmer/Decca/Youtube

University over, the young Shirley-Quirk was headed for a career in industrial chemistry, “I hated it” he says, simply. “But I joined the airforce – their education branch – which was based in Melksham, Wiltshire. I was teaching the physics of flight to RAF folk. Whilst I was there I was introduced to a man called Fritz Spiegl, who was the Principal Flute in the Liverpool Philharmonic. I sang in some concerts for him. He then wrote to a friend of his family, called John Olive, who lived in Shawford House, just outside Bath. I was married at the time to a trainee doctor at the RUH in Bath. John and Phyllis Olive were to become very, very important in my life. We started singing, and he built an opera house in Shawford Mill. So you see, I’ve come full circle. One day Phyllis Olive took me aside and told me that I was going to teach in London. So I had an audition with Roy Henderson, who had just had tremendous success with Kathleen Ferrier. There I was, studying, trying to learn how to sing by night and by day teaching chemistry at Acton Technical College, which later went on to become Brunel University. Shirley-Quirk was one of their founder members, “I’m very proud of being a Doctor of Science at Brunel – and a Doctor of Music at Liverpool University, ” he smiles.

Then came a period of “stressful overlap”, he explains, “a moment when I had to decide. I began to feel Jekyll and Hyde parts of me pulling in different directions. In the end I finally put in my resignation and was more or less simultaneously offered a role in Hans Werner Henze’s “Elegy for Young Lovers” at Glyndebourne. The year was 1961 and it was the opera’s first English performance, translated from the original German. So there I was, learning new opera by day and marking final exam papers for Acton in the evening. I was told by a colleague that they had re-marked all my papers they were such a mess. I was young and foolish…” Soon after this Shirley-Quirk found himself singing Bach, alongside a tenor called Peter Pears with the Ipswich Bach Choir under the baton of a Dr Merlin Channon. “It was the Christmas Oratorio. At the end of the performance a man came up to me and told me that he’d very much enjoyed my D major Aria. That man turned out to be Benjamin Britten. Within eighteen months I was engaged to sing the role of the ferryman in his opera, „Curlew River.“ It was fantastic. Quite extraordinary. A wonderful experience…Peter Pears and I worked a tremendous amount together after that. I had roles written for me from ‘Curlew’ onwards. I was working more or less on and off all the time with them from then on…” It was a musical partnership that was to define his career and endured right up until the time of Britten’s death from heart failure in 1976. “Peter Pears,( Britten’s partner and life-time companion), and I sang Bach together often accompanied by Britten. We sang the „St John’s Passion“ and the „Christmas Oratorios“ in the native German – so much better in the original language. Translation is contortion. You lose, you cannot but lose, by translation. However, there is some room for the argument that you should make room for two versions – go hear the text properly firstly, then go and hear the same piece in the original language. It is always so much the richer.”

Shirley-Quirk performed with Peter Pears at the premiere of Britten’s ‘Curlew River’ at St Bartholomew’s Church, Orford, Suffolk on 13th June, 1964. The opera was to mark a departure for Britten, making way for the operas, ‘Owen Wingrave’ and ‘Death in Venice’ that were to follow later. Shirley-Quirk singles both these operas out as milestones in his musical career, “Curlew River put me on the musical map – which was hair-raising. But I suppose that I have the greatest affinity with the role of Spenser Coyle in ‘Owen Wingrave’. (which premiered at Britten’s beloved Snape Maltings – and was also recorded for television in two parts – in November 1970. Like ‘Turn of the Screw before it, it was an adaptation of a Henry James short story) It was the role that Britten wrote for me, it fitted me like a glove. He told me, ‘There’s an awful lot of you in it…essence of you.’ I had the role of the man who saw both sides of the problem – Wingrave the pacifist, his familys’ rejection of this, and his subsequent mysterious death. The role was very precious to me.” Shirley-Quirk knew only too well the disruption and chaos of war, perhaps not too clunky a point to make here. Britten was a committed pacifist. (His ‘War Requiem’, first performed at the reconsecration of Coventry Cathedral in May, 1962, is interwoven with nine poems by the war poet, Wilfred Owen. John Shirley-Quirk later recorded the work with the London Symphony Orchestra and the choristers of St Paul’s Cathedral, conducted by Richard Hickox on the Chandos label.)

Three years later and Shirley-Quirk was back at Snape Maltings performing alongside Peter Pears in the premiere of Britten’s most famous opera, Death in Venice, based on the novella by Thomas Mann. The date was 16th June, 1973 and it was to be Britten’s last opera. John explains, “This was the work that brought international acclaim and attention – particularly in America. We finished up doing more performances there than anywhere else, infact. Shirley-Quirk took several roles within the opera, a traveller, an ‘elderly fop’, an old gondolier, a hotel manager, a hotel barber, a leader of a group of players – and the voice of Dionysus. Britten wove him deep into the fabric of the opera.

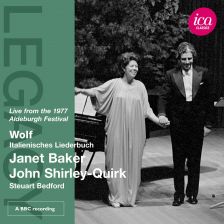

Shirley-Quirk went on to record and perform under all the legendary conductors of the second half of the twentieth century, including Sir Georg Solti, with whom he recorded Mahler for the Decca label; he has performed Tippett, including the premiere of ‘The Vision of St Augustine’ in 1971, and sung all the legendary bass-baritone roles on a world stage, from Covent Gardens’ Royal Opera House, to Sydney, to Vienna to New York and back again. But it is to Britten and Snape Maltings at Aldeburgh that he returns as he talks of his defining moment as a performer, “I think it was at Aldeburgh that I did my best work, my best performances. Peter Pears and I sang together in a performance of Schubert’s posthumous ‘Schwanengesang’, which translates as ‘Swan song’. Ben played piano. I think that that was possibly the peak of my career. Britten at the time was possibly the greatest accompanist in Europe. We also sang ‘The Songs and Proverbs of William Blake’ – a first performance of a cycle of early works. And a short cycle of Wolf’s ‘Michelangelo Lieder’. “I suppose you could call me a ‘torch bearer’ for Britten, as a teacher for what Britten’s music is about and how it should be approached.”

Shirley-Quirk went on to record and perform under all the legendary conductors of the second half of the twentieth century, including Sir Georg Solti, with whom he recorded Mahler for the Decca label; he has performed Tippett, including the premiere of ‘The Vision of St Augustine’ in 1971, and sung all the legendary bass-baritone roles on a world stage, from Covent Gardens’ Royal Opera House, to Sydney, to Vienna to New York and back again. But it is to Britten and Snape Maltings at Aldeburgh that he returns as he talks of his defining moment as a performer, “I think it was at Aldeburgh that I did my best work, my best performances. Peter Pears and I sang together in a performance of Schubert’s posthumous ‘Schwanengesang’, which translates as ‘Swan song’. Ben played piano. I think that that was possibly the peak of my career. Britten at the time was possibly the greatest accompanist in Europe. We also sang ‘The Songs and Proverbs of William Blake’ – a first performance of a cycle of early works. And a short cycle of Wolf’s ‘Michelangelo Lieder’. “I suppose you could call me a ‘torch bearer’ for Britten, as a teacher for what Britten’s music is about and how it should be approached.”

For the last twenty years, until his recent return to Bath, the city of his musical metamorphosis into a professional performer, Shirley-Quirk was doing just that, teaching the next generation of singers as a faculty member at the prestigious Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore. He explains the reason for leaving England for America, “I was married at the time to an American oboeist. She was very unhappy living here in the UK so we moved to both work at Peabody. I even took dual nationality after 9/11 for some quixotic reason. I felt that they were under attack, we were all under attack. I ought to join them. It felt as if western civilisation were under attack.”

Shirley-Quirk went on to explain his philosophy of performance and the music which has informed his life, “Music is a language. When you put two languages together simultaneously there should be a great affinity between them. The act of getting a musical idea down on paper in the usual format – a series of dots – is extremely imprecise. It is a skeleton of what the music is trying to express. For every composer these ‘dots’ have to be clothed in flesh by the performer. And a performer my main struggle is to understand the composer. How to interpret these little black dots? There they are. How do you interpret them? And it’s different with every composer. That is the delight of being a performer – trying to understand the composers. It ought to be a struggle. It is not straightforward. If you hear a sentence on the phone you are missing the body language. The piece of music is just a telephoned message, really. For me the body language is missing. As a performer it is your job to find it. This is the constant search for meaning. During performances your concentration is on what is coming next – which makes it very difficult to be ‘in the moment’. You are thinking in two very special places at once. Music is very much a matter of playing with time. You are dealing with the very moment – and the immediate future. The trick is to be able to do that. To co-exist on different time scales.”

Shirley-Quirk gave his last public performance some six and a half years ago at the Edinburgh Festival, “I was one of the ‘golden oldies’ in ‘Die Meistersinger’” he smiles, “I had no idea that it would be my last.” Living in Bath now, surrounded by generations of his family with his third wife, Terry, a cellist, Shirley-Quirk is indeed a man come full circle. The final words must, of course, be his, “To think back on all the huge pleasure it’s been, the blood, sweat and tears too. The memories are wonderful…” …