Rockwell Blake ist und war einer der ganz großen Sänger für Rossini und den Belcanto. Ohne ihn wäre die Rossini-Renaissance ab Mitte der 1980er-Jahre nicht in Gang gekommen. Sein Beitrag zu diesem Repertoire ist unschätzbar. Im Tandem mit dem Tenor-Kollegen Chris Merritt schuf er die wunderbaren Rossini-Opern für die beiden legendären Tenöre David (Blake) und Nozzari (Merritt) nach und hinterließ ebensolche legendäre Spuren.

Ich muss gestehen, dass ich ihm nachgereist bin, um ihn in der Donna del Lago, Zelmira oder Ermione zu hören – in Parma, Rom oder Pesaro. Einen Sänger wie ihn gab´s nicht vorher und nicht wieder, Flórez hin oder her. Blakes Timbre mag Geschmackssache sein (ich hatte damit nie ein Problem, und jeder hört anders), aber wie bei der Callas vergaß man nach wenigen Minuten die Farben und dass er überhaupt sang und war hingerissen von der Kunst: von seiner Bombentechnik, von der interpretorischen Sicherheit und der soliden Schauspielkunst des amerikanischen Tenors. Alles schien bei ihm selbstversändlich und leicht zu sein, wenngleich ich ihn mal in Santiago de Chile vor dem zweiten Akt der Sonnambula hin und her tigern sah und seine charmante Frau Debbie (what a great woman und ex-Sopran) leise zu mir sagte: Er hat Bammel wegen des Concertato-Ensembles „Lisa ….“ am Schluss. Rockwell Blake nervös zu sehen war die Reise wert, das kannte ich nicht von ihm, der stets so souverän und gelassen wirkte.

Ich habe Rocky Blake viele wunderbare Abende zu verdanken, in so vielen Städten der Welt, meist mit Rossini, wo ich ihn am liebsten hörte. Auch im Französischen (sein Pariser Robert le Diable ließ vor Beifall die ehrwürdige Salle Garnier erbeben) und in anderen Belcanto-Partien, mit wunderbaren Partnern wie der Cecilia Gasdia, Samuel Ramey, Lucia Valentini Terrani, Kathleen Kuhlmann, Lella Cuberli (June Anderson lasse ich jetzt einfach aus), Roberto Servile und viele, viele mehr. Er war und ist für mich der Inbegriff eines hochflexiblen Künstlers, der sein Medium ideal beherrschte, der nie über seinem Vermögen sang, der mit Humor Nähe schaffte, der mit seiner Frau zusammen ein bezauberndes, gastfreundliches und ebenso professionell freundliches wie liebenswürdiges Paar war. Es gibt und gab keinen wie ihn.

Ich nahm eher durch Zufall den Kontakt mit ihm wieder auf, weil wir uns aus den Augen verloren hatten. Als sich per mail unsere Wege kreuzten, las ich, dass er nicht nur immer noch an Autos rumbastelt (er hat eine geniale Hand für Technik), sondern dass er unterrichtet und sein Wissen weitergibt. Im Folgenden also das Interview zwischen Berlin und Turin mit dem Helden meines Rossini-Coming-Outs der Achtziger. Danke Rocky. Geerd Heinsen

Nun also Rockwell Blake direkt (eine kurze Bio gibt’s am Ende): Singing takes intelligence (well sometimes) – has an intelligent singer an advantage over a dumb one. You repudiated the image of the dumb tenor and have excelled in knowing your voice, your technique and your ambience. does that help? Being able to think clearly is the best advantage a brain can offer a singer. If a singer is confused he or she will get lost. Dumb singers who are successful are not dumb. They just put up the dumb front and hide behind it.

What I did with my voice, mind and heart in the music world was to make the best performance I could under every circumstance. It was because of this desire to always do my best that I learned how much I didn’t know when I started out. So I decided I would never stop learning. I am still learning about singing by learning how to teach others to do their best.

Smart singers who take advantage of dumb singers are only diminishing the overall quality of the performance in which they are performing. I would call it a form of theft. The smart fool is steeling value from the ticket buying public, when he should be helping the dummy be as successful as possible.

You sang mainly (but of course not exclusively) Rossini: what does it take to be a good Rossini tenor? What kind of voice is require (Davide and Nozzari and all that)? How important is technique (maybe a word about a sound technique at all)? Maybe a word about Rossini in contrast to – say – other (later/ belcanto) composers? How long can a singer sing this acrobatic repertoire? A good Rossini tenor is one who can make his performance of this composer’s music satisfy his audience and stand as a unique interpretation. Then at the next performance do the same for a new audience and make enough variations from the previous performance to satisfy those audience members who also attended the previous performance. If he can do that, then he is a good Rossini tenor.

The category of voice is not at issue. Rossini wrote music for as many different kinds of tenors as we have today. David was lyric. Nozzari was dramatic. There were others of similar and differing categories who were to be Rossini’s first love interests or heroes or villains in his scores. The technique necessary was well understood in Rossini’s day. How to teach it was a bit controversial, but the son of Rossini’s first Almaviva wrote down most everything we need to know about the technique Rossini’s favorite singers used. The same technique supported the full run of the Bel Canto composers.

The ability to sing fast notes is no less perishable than the ability to run fast 1000 meter races. The singer doesn’t have to be the fastest to win. He just has to be effective enough to win his audience. Time will always sneak up on you. As long as you can sell Rossini’s music to an appreciative audience, who is going to kick you out?

Technique and diction/recitaves? I remember you pacing up and down in Santiago before the last act of Sonnambula and „fearing“ the finale with the ton up and up – again how important is technique? I wish I could place my pacing. I’m at a loss to understand where that groove in the floor might be that my pacing created. I do admit to nerves concerning my memory, and naming recitatives as a preamble inspires me to think it was my memory that threatened to make my life on the stage difficult enough to cause me to pace. Anyway, technique and diction are things that should be settled issues. Remembering the words in endless recitatives in Opera Seria can be a huge problem. I always suffered from a very lazy memory. My technique was well organized by the time we began to enjoy your company in the theatre. My diction won compliments from most quarters, but if I couldn’t remember the words, who cares if I could pronounce them like a native.

As we are talking about Rossini – a word (if you dare) about the present state of affairs? Voices too light? I like Spyres (of the many he seems for me the only one apropriate for a Rossini tenor, and Flórez not really for the heroic repertoire). Is there a difference to theatres and audiences nowadays as against your time (not so long ago I know, but i think the Rossini Renaissance is over more or less…). The Rossini Renaissance had to give way in the face of the trends that were visible even when I was on top of my game. There is a problem, and it is systemic. I see an industry in crisis and it seems to want to blame the audience. The product that the industry is presenting is the problem, and the singers who walk out onto the stage in the productions the industry sees fit to offer the audience are just not ready for prime time. The industry and the system by which singers are prepared are at fault. The audience is just making their choices according to what they like.

Your other love was French opera – the difference in singing between the italians and the french? Again diction, different sounds/nasals/consonants? more on French opera? In the past two weeks I have been talking about this dichotomy a lot. The French style is like night to the sunny Italian style. Technically they are different challenges, and I like to call the French style easy to understand if you know what Italian style is. All you really have to do is turn Italian style on its head and you have French style.

Good diction is necessary, but the crispness of movement from one pure vowel to another in Italian gives way to elisions and smoother and slower vowel transitions in the French. The French style of expressing love in song is more sophisticated than the Italian style. Just today I was struggling to explain to a tenor, well acquainted with Italian style, how differently he should sing a French phrase. I ended up creating an argument between two groups of singers. One group from the French school and another from the Italian school. The Italians would insult the French for the mannerisms that they would employ while singing the phrases written for them by French composers, and the French group would laugh at the Italians extreme hard work to even sing the notes while making a mess of the delicate French phraseology. I spoke for both groups and demonstrated the vocal differences which included the wrong headed manner of attack that the normal Italian school devotee’ would make on the poor French composer’s music. All of this was a little pathetic in light of the fact that both of these schools seem to have disappeared.

What does an intelligent opera singer do after not singing any more? Repairing oldtimers? Teaching? How gratifying is teaching? How can one convey the sense of theatre? Acting? You were a very sound and commited actor – how does one get that across? How is the state of things in preparation of the kids? Teaching is a small part of what I do and it is like eating candy. The more you eat the more you want. I have a wonderful time pushing students to be theatrical. There is nothing like the look on the face of a singer who breaks through personal inhibitions and manages to express the emotions of the character for whom the aria in question was written. It is almost like discovering a new world, landing on the Moon or finding a diamond wedged in a crack in the sidewalk under his/her feet.

The state of affairs is what I could see coming a long time ago. Manuel Garcia saw it coming near the end of his long life. I think of myself as a small voice of reminder that the old ways are good. What is new is not bad because it is new. It is bad because it is not enough.

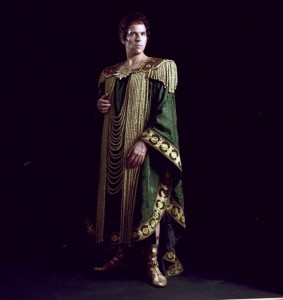

Und dazu der Beitrag des verdienstvollen Wikipedia-Eintrags: Rockwell Blake (born January 10, 1951) is an American operatic tenor, particularly known for his roles in Rossini operas. He was the first winner of the Richard Tucker Award. Born and raised in Plattsburgh, New York, Blake was the son of a mink farmer.[1] After graduating from high school in the nearby town of Peru, he studied music first at the State University of New York at Fredonia and then at The Catholic University of America. On leaving Catholic University, he served for three years in the United States Navy as a member of the Sea Chanters male chorus and later as a soloist with the US Navy Band.

During that time, he continued his voice training with Renata Carisio Booth, who had been his teacher since his school days. He made his solo opera debut in 1976 at the Kennedy Center in Washington D.C. as Lindoro in Rossini’s L’italiana in Algeri, and made his debut at the New York Metropolitan Opera House in 1981 in the same role, with Marilyn Horne as his Isabella. He went on to become one of the leading Rossini singers of his generation, singing regularly at the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro since his debut there in 1983. He made his La Scala debut in 1992 as Giacomo in La donna del lago. It was La Scala’s first production of the opera in 150 years and was staged to mark the bicentenary of Rossini’s birth.

His two-and-a-half octave range and mastery of florid vocal technique and coloratura, have made him a successful interpreter not only of Rossini’s tenore contraltino roles (in whose recent revival he has been a chief protagonist), but also of operas by Mozart, Donizetti, Bellini and Handel. Within that repertoire, Blake has sung in over 40 operas, including relative rarities such as Rossini’s Zelmira, Mozart’s‘ Zaide, Donizetti’s Il Furioso all’Isola di San Domingo, Haydn’s L’Infedelta Delusa and Boieldieu’s La Dame blanche. Blake has also been active in the orchestral and oratorio tenor repertoire, performing in works by Bach, Beethoven, Berlioz, Britten, Handel, Haydn, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Rossini, Saint-Saëns, and Stravinsky.

Since 2001 he has increasingly devoted himself to teaching and has given master classes at the Associazione Lirica Concertistica Italiana in Milan, the Conservatoire Nationale de Paris, the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome, Duke University in North Carolina, the State University of New York, the Hamburg Staatsoper, and the Chicago Lyric Opera young artists program. His last appearances on the opera stage were as Uberto in Rossini’s La donna del lago (Lisbon, 2005) and as Libenskoff in Rossini’s Il viaggio a Reims (Monte-Carlo, 2005)

Prizes and distinctions[edit]: Richard Tucker Award 1978/ Cavaliere Ufficiale, Ordine al/ Merito della Repubblica Italiana 1994/ Diapason d’Or de l’Anné 1994/ Honorary Degree – Doctor of Music, State University of New York/ Victoire de la Musique 1997/ Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et Lettres de la République Française 2000/ Grand Prix du Palmares des Palmares 2004

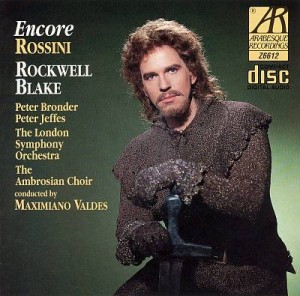

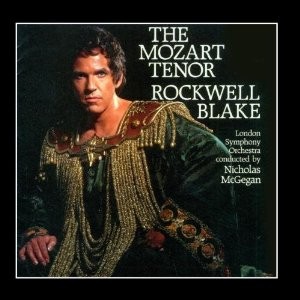

Discography/ Boieldieu – La Dame blanche, Conductor Marc Minkowski (CD Angel/EMI)/ Donizetti – Alina, Regina di Golconda, Conductor Antonello Allemandi (CD Nuova Era)/ Donizetti – Marin Faliero, Conductor Ottavio Dantone (DVD Hardy Classic)/ Mozart – Mitridate Re di Ponto, Conductor Theodor Guschlbauer (DVD Euro Arts)/ Rossini – Il barbiere di Siviglia, Conductor: Bruno Campanella (CD Nuova Era)/ Rossini – La Donna del Lago, Conductor: Riccardo Muti (CD Philips)/ Rossini – La Donna del Lago, Conductor: Riccardo Muti (DVD La Scala Collection)/ Rossini – La Donna del Lago, Conductor: Claudio Scimone (CD Ponto)/ Rossini – Elisabetta Regina d’Inghilterra, Conductor Gabriele Ferro (DVD Hardy Classic)/ Meyerbeer – Robert le Diable, Conductor Thomas Fulton (DVD Encore)/ Airs d’Opéras Français (CD EMI)/ The Rossini Tenor (CD Arabesque Records)/ Encore Rossini (CD Arabesque Records)/ The Mozart Tenor (CD Arabesque Records)/ Rossini Melodies (CD EMI)