Mehr als 80 (!!!) Klavierkonzerte und viel Aufregendes sonst noch auf dem Klavier aus der romantischen (aber auch spätromantischen, zum Teil zeitgenössischen) Ära bietet die neue Box mit 40 (!) CDs bei Brilliant Classics. Erstaunlicherweise sind eigentlich weniger die bekannten wie die von Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Weber & Co. vertreten, sondern es finden sich so seltene Namen wie Kozeluch, Field, Piatti, Kuhlau, Tailleferre, Mason, Alkan, Berwald oder Vogler, sogar Simone Mayr unter den hier vertretenen Komponisten. Und zu den echten Klavierkonzerten kommen solche Leckerln wie Africa von Saint-Saens oder die Ode an den Frühling von Joachim Raff! Neben Balakireff oder Rubinstein liegt hier der große Reiz, Unbekanntes auf dem und für das Klavier kennen zu lernen. Die Ausstattung ist mäßig: karg bedruckte Pappschuber für die einzelnen CDs mit nur den elementarsten Angaben und ein dünnes Beilageheftchen mit einem nur englisch gehaltenen Aufsatz, der sehr kursorisch die Werke/ Komponisten behandelt. Aber für den geringen Preis ist dies hier eine wirkliche Trouvaille (40 CDs Brilliant Classics 95300) . G. H.

Dazu schreibt Brilliant Classics auf ihrer Homepage: Nicht die Sinfonie, die mit Mozart, Haydn und vor allem Beethoven ihren Höhepunkt erlebte, sondern das Klavierkonzert wurde zur liebsten Gattung der romantischen Komponisten im 19. Jahrhundert. Zum einen gab es in der Generation nach Beethoven einen gehörigen Respekt vor dem sinfonischen Kanon, den die Wiener Klassik vorgelegt hatte, zum anderen entwickelte sich parallel mit der steten Verbesserung des modernen Klaviers auch eine neue Virtuosenkultur am Konzertflügel. Durch Europa reisten Dutzende Pianisten, die um die Gunst des Publikums buhlten. Der Hunger nach virtuosen Musikern war ebenso groß wie der Bedarf an neuen, unverbrauchten Konzerten, die die Solisten ins rechte Licht rückten und die dem Gusto des Publikums zusagten.

Dazu schreibt Brilliant Classics auf ihrer Homepage: Nicht die Sinfonie, die mit Mozart, Haydn und vor allem Beethoven ihren Höhepunkt erlebte, sondern das Klavierkonzert wurde zur liebsten Gattung der romantischen Komponisten im 19. Jahrhundert. Zum einen gab es in der Generation nach Beethoven einen gehörigen Respekt vor dem sinfonischen Kanon, den die Wiener Klassik vorgelegt hatte, zum anderen entwickelte sich parallel mit der steten Verbesserung des modernen Klaviers auch eine neue Virtuosenkultur am Konzertflügel. Durch Europa reisten Dutzende Pianisten, die um die Gunst des Publikums buhlten. Der Hunger nach virtuosen Musikern war ebenso groß wie der Bedarf an neuen, unverbrauchten Konzerten, die die Solisten ins rechte Licht rückten und die dem Gusto des Publikums zusagten.

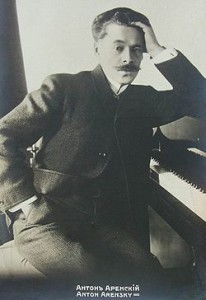

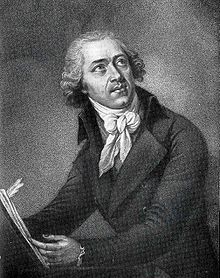

Während im Rückblick sich nur relativ wenig Namen und Konzerte im Repertoire halten konnten, war das tatsächliche Output viel größer. Die 40-CD-Box „Romantic Piano Concertos“ verschafft dem Musikfreund die Möglichkeit, sich einen ausführlichen Überblick über das durchgehend hohe Niveau der Klavierkonzerte der vermeintlich „kleinen Meister“ zu verschaffen. Dabei reichen die zusammengefassten Kompositionen von der Vorromantik mit Werken von Vogler, Viotti und Tomášek über die Frühromantik der Beethoven-Freunde und Schüler wie Clementi, Cramer und Czerny bis zur breit gefächerten Hoch-Zeit der Romantik. Konzerte von Berwald, Field, Hiller, Hummel, Moscheles, Pierné, Raff, Rubinstein, Saint-Saëns und Thalberg bilden den Schwerpunkt der Sammlung. Besonders interessant sind auch die Konzert-Raritäten von Arensky, Balakirev, Glazunov und Rubinstein. Neben einigen Raritäten auch bekannter Namen wie Chopin, Dvořák, Liszt, Mendelssohn, Schumann und Tschaikowsky enthält die Box auch Aufnahmen der von der Romantik beeinflussten Konzerte von Respighi, Gershwin und Barber. Insgesamt umspannt die Sammlung über 100 Werke aus rund 200 Jahren von mehr als 60 Komponisten.

Während im Rückblick sich nur relativ wenig Namen und Konzerte im Repertoire halten konnten, war das tatsächliche Output viel größer. Die 40-CD-Box „Romantic Piano Concertos“ verschafft dem Musikfreund die Möglichkeit, sich einen ausführlichen Überblick über das durchgehend hohe Niveau der Klavierkonzerte der vermeintlich „kleinen Meister“ zu verschaffen. Dabei reichen die zusammengefassten Kompositionen von der Vorromantik mit Werken von Vogler, Viotti und Tomášek über die Frühromantik der Beethoven-Freunde und Schüler wie Clementi, Cramer und Czerny bis zur breit gefächerten Hoch-Zeit der Romantik. Konzerte von Berwald, Field, Hiller, Hummel, Moscheles, Pierné, Raff, Rubinstein, Saint-Saëns und Thalberg bilden den Schwerpunkt der Sammlung. Besonders interessant sind auch die Konzert-Raritäten von Arensky, Balakirev, Glazunov und Rubinstein. Neben einigen Raritäten auch bekannter Namen wie Chopin, Dvořák, Liszt, Mendelssohn, Schumann und Tschaikowsky enthält die Box auch Aufnahmen der von der Romantik beeinflussten Konzerte von Respighi, Gershwin und Barber. Insgesamt umspannt die Sammlung über 100 Werke aus rund 200 Jahren von mehr als 60 Komponisten.

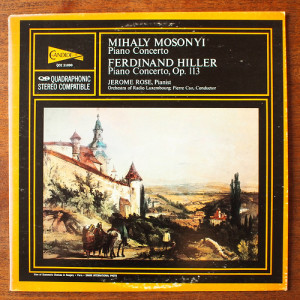

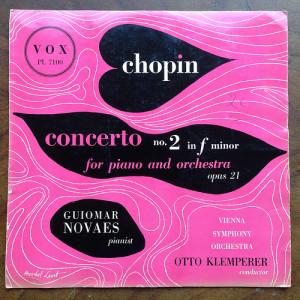

Den Grundstock für die Sammelbox bilden Archivaufnahmen des US-amerikanischen Vox-Labels. Dieses war in 1960er und 1970er Jahren dafür bekannt, Aufnahmen von Werken auch abseits des üblichen Katalogs zu veröffentlichen. Solisten wie Michael Ponti, Felicja Blumenthal, Eugene List, Marylène Dosse, Rudolf Firkušny und Roland Keller bürgen für höchste Qualität. Klangkörper wie das Berliner Sinfonie-Orchester, das Orchestra of Radio Luxembourg, die Philharmonia Hungarica, die Wiener Symphoniker unter der fachkundigen Leitung von Dirigenten wie Antal Doráti, Louis de Froment, Jörg Faerber, Herbert Kegel und Alberto Zedda sorgen für eine erstklassige Begleitung.

Bei vielen der hier zusammengefassten Aufnahmen handelt es sich um konkurrenzlose Weltersteinspielungen, die teilweise jahrelang nicht mehr erhältlich waren. „Romantic Piano Concertos“ ist ein Muss für jeden Sammler, ein regelrechter Schatz für alle Raritätenjäger, ein zu entdeckender Fundus ungerechterweise vernachlässigter Werke, die nun endlich wieder erhältlich sind. (Quelle Brilliant Classics)

Bei vielen der hier zusammengefassten Aufnahmen handelt es sich um konkurrenzlose Weltersteinspielungen, die teilweise jahrelang nicht mehr erhältlich waren. „Romantic Piano Concertos“ ist ein Muss für jeden Sammler, ein regelrechter Schatz für alle Raritätenjäger, ein zu entdeckender Fundus ungerechterweise vernachlässigter Werke, die nun endlich wieder erhältlich sind. (Quelle Brilliant Classics)

Und dazu der Artikel aus dem beiliegenden Booklet: Romantic Piano Concertos – the standard repertoire of piano concertos from the Romantic period comprises about two dozen works at most. This represents no more than a tiny fraction of the total number of works belonging to this genre. The hundreds of non-repertoire ‚also-rans‘ include neglected works by well-known composers – say Tchaikovsky’s Third Piano Concerto or the 1st, 3rd, 4th and 5th Concertos by Saint-Saens – and concertos by the overwhelming number of almost completely forgotten composers: Moscheles, Moszkowski, Scharwenka, Hiller, Thalberg, Stavenhagen, Reinecke, D’Albert and Amy Beach, to name but a few. To yet another category belong the numerous compositions, less ambitious than a concerto but nevertheless fine works, which are rarely programmed because of their less convenient length or a less marketable title, such as Concert Fantasy, Fantaisie or Konzertstiick. Weber’s Konzertstiick, for instance, is a quasi-symphonic poem which strongly influenced Romantic composers and even Stravinsky. Equally, Schumann’s Introduction and Allegro appassionato, Liszt’s Totentanz and Cesar Franck’s Symphonic Variations are all richly characteristic of the genius of their respective composers. Also includable as another category or type is the piano concerto by a composer more readily associated with an instrument other than the piano – such as Rheinberger and the organ or Viotti and the violin. (It has been claimed that the Viotti Concerto in G minor on CD24 is an original piano concerto, though it may be an arrangement of one of his 29 violin concertos).

„Romantic Piano Concertos“ bei Briliant Classics: Anton Ahrensky/ Wiki

Among the very earliest of all keyboard concertos are those written for Cristofori’s new fortepiano by Giovanno Benedetto Platti; born around 1692, not long after Bach and Handel, he died in 1763. Clementi’s only piano concerto dates from 1796, while concertos by Hoffmeister, Stamitz, Paisiello and others were all composed in the last decades of the 18th century. Although such works, like Mozart’s piano concertos, are essentially Classical, one may sometimes detect elements which anticipate the early Romantic period. However, it was only around the onset of the 19th century that composers in general began to assimilate qualities which we now describe as Romantic, at the expense of the restraint, symmetry and clarity of the Classical period.

The term ‚Romantic Piano Concerto‘ clearly signifies the Romantic period of musical history, but such a restriction would be an over-simplification. Many composers – so-called ‚late-Romantics‘, including Barber, Respighi, Medtner and Dohnanyi – continued to write in a basically 19th-century (or Romantic) idiom well into the 20th century. In any case, dividing lines between periods are rather artificial and approximate, as we find when we try to classify the mature music of Beethoven or Schubert – both an amalgam of Classical and Romantic characteristics. We should remember that such terms, alongside others including sonata form, became commonly used only by later generations.

Dublin-born John Field, considered the greatest pianist of his day, may be regarded as a true early Romantic. Few genres are as typical of the Romantic period as the nocturne, of which Field composed eighteen examples for solo piano, while the central movements and other passages from his seven piano concertos also are nocturne-like. Chopin is the first composer who comes to mind in connection with the nocturne, a genre which he developed, refined and perfected. Yet his supremely poetic piano-writing in his own solo works, his two concertos and the various shorter pieces such as the Andante spianato et grande polonaise brillante, shows the influence of Field, as well as that of Bellinian bel canto. Field was one of the first of a long line of virtuoso performers who composed for the piano with greater freedom and poetic imagination.

„Romantic Piano Concertos“ bei Briliant Classics: Edward MacDowell/ Wiki

Hummel (an almost exact contemporary of Field’s) was another virtuoso – one of the greatest of his day. His 1828 publication A Complete Theoretical and Practical Course of Instruction in the Art of Playing the Piano Forte was a landmark, setting out a new method of fingering and the playing of ornaments. 19th-century piano technique was greatly indebted to Hummel, who taught Czerny, who in turn taught Liszt. Hummel (a pupil of Mozart) composed eight piano concertos, of which the more mature works such as those in A minor and E major were admired by Chopin and other Romantic composers. Indeed, Hummel’s A minor Concerto and the roughly contemporary B minor Concerto Op. 89 were standard repertoire works of the early 19th century, studied and performed by the majority of budding virtuosos. Weber’s two concertos, while not as strikingly original as his Konzertstiick, are typically lyrical examples of early Romanticism.

Important factors which contributed to ‚the age of the virtuoso‘ were the revolutionary developments in piano construction, with an increase in compass (from five octaves to seven and a quarter) and other improvements which facilitated rapid playing and allowed much greater resonance. Now the piano was a rather different beast from the instrument constructed by Cristofori about 100 years previously. It is easy to understand how the exciting potential of the new instrument inspired composers to exploit its various qualities, sometimes for their own sake.

As the aftermath of the French Revolution led to far-reaching social change, the piano’s realm expanded from domestic music-making to the wider world of the public concert, and this was another development which encouraged the public appeal of the virtuoso. Alongside the violin, elevated onto an unprecedented technical level by the wizardry of the charismatic Paganini, the piano became equally popular as a virtuoso concerto instrument – a showcase for the performer or composer/performer. Both Mozart and Beethoven had performed their own concertos, but now a new, more flamboyant kind of pianist emerged.

„Romantic Piano Concertos“ bei Briliant Classics: Gerog Joseph Vogler/ Wiki

Sir George Grove wrote in 1899: ‚Virtuoso is a term of Italian origin, applied more abroad than in England, to a player who excels in the technical part of his art. Such players being naturally open to a temptation to indulge their ability unduly at the expense of the meaning of the composer, the word has acquired a somewhat deprecatory meaning, as of display for its own sake … virtuosity is the condition of playing like a virtuoso. Mendelssohn never did. Mme Schumann and Joachim never play in the style alluded to. It would be invidious to mention those who do.‘ Against this may be balanced Saint-Saens‘ eloquent words on the expressive potential of virtuosity: ‚A powerful aid to music, whose range it extends enormously‘ … ‚it gives the artist wings to help him escape from the prosaic and commonplace‘ … ‚the conquered difficulty is itself a source of beauty‘.

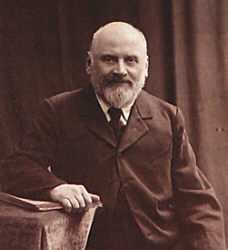

Hiller, Moscheles, Kalkbrenner, Czerny, Thalberg, Henselt and Cramer (whom Beethoven considered the finest pianist of his day) are all among the most famous 19th-century virtuosos. The extremely prolific Czerny (over 1,000 works) may be remembered for his studies but his Concerto in A minor (cl830) is a far from negligible work with piano-writing evoking comparison with early Chopin. The Piano Concerto in G minor by Moscheles (who taught Mendelssohn) is a fine work which Chopin admired, while Schumann, though despising the fashionable kind of empty virtuosity associated with Kalkbrenner and other contemporaries, nevertheless did perform Kalkbrenner’s Piano Concerto in D minor Op.61.

In the early nineteenth century the Viennese were infatuated with Thalberg’s virtuosity, though his early Concerto in F minor is lyrical and actually not outrageously difficult. Thalberg became a strong rival to Liszt. In 1836 Parisians divided into Thalbergian and Lisztian factions, and the following year both pianists contributed to a benefit concert for refugees which virtually amounted to a public duel. If we do not expect every composer – whether Bronsart, Kalkbrenner, Cramer, etc. – to be a genius comparable with Chopin, Schumann or Mendelssohn, we may enjoy the superbly idiomatic, often fiercely demanding piano-writing and consider Saint-Saens‘ words about ‚the conquered difficulty‘ being ‚a source of beauty‘.

Virtuosity became one of the defining qualities of the Romantic period, a period in which self- projection was taken to a new level. Paganini’s impact upon numerous composers – including Schumann and Liszt – cannot be overestimated. This period, in which the cult of the personality burgeoned, is distinguished by a new emphasis on the performer as hero.

In addition to his celebrated five piano concertos, Beethoven wrote at the age of 14 a Piano Concerto in E flat and more than 20 years later he made a piano arrangement of his Violin Concerto. Bizarrely this includes a cadenza with prominent timpani. Ries, a pupil of Beethoven but subsequently his secretary and copyist, wrote eight piano concertos of which No.3 is among the most impressive. This is a characterful work distinguished by charm, elegance, at times a beautiful simplicity, and superb piano-writing throughout. If we expect this concerto to be heavily influenced by Beethoven, we may well be surprised by the individuality of Ries‘ own musical personality.

„Romantic Piano Concertos“ bei Briliant Classics: Ignaz Moscheles/ Wiki

Mendelssohn’s two concertos are among the finest of the early Romantic period. Both concertos accommodate brilliance and, in their respective slow movements, tender emotion. Mendelssohn also wrote shorter works such as the Capriccio brillant and an early Concerto in D minor for piano, violin and strings (1823) which shows his uncanny teenage facility. At the beginning of his second Piano Concerto in D minor, Mendelssohn, in Joseph Kerman’s words, ‚plunges immediately into an evolving drama, a relationship at work‘. This description raises the question of the role of the pianist – i.e. the nature of the piano-orchestra relationship, encompassing many different approaches. Generally these relationships became more piano-centred in the Romantic period, but in his excellent book Concerto Conversations Kerman discusses them and suggests apt names such as ‚polarity‘ or ‚reciprocity‘.

The Frenchman Alkan, an astonishing prodigy admitted to the Paris Conservatoire at the age of six, whom Liszt believed to possess ‚the finest technique of any pianist known to him‘, composed a vast number of highly original and phenomenally difficult solo piano pieces. His Concerto da camera No.2 in C sharp minor is a ten minute work with some extraordinarily virtuosic writing. The Swedish Berwald may appear an outsider among the mass of Central European composers of piano concertos, but he did study in Berlin and later moved to Vienna, returning to Sweden in 1849 to manage a glassworks. His Piano Concerto, dating from 1855 but unperformed until 1904, is not as striking as some of his symphonies, but nevertheless is a lyrical work which deserves to be heard.

Liszt is a legendary figure who, stunned by the playing of Paganini, transformed the public’s awareness of the piano’s potential – both technically and in its range of tone-colours. He commanded an extravagant spectrum of quasi-orchestral sounds, including shimmering effects, bell imitation and other innovatory sonorities. Liszt’s influence on so many subsequent composers for the piano (including Lyapunov, Saint-Saens, Albeniz and Busoni) – merely in terms of his extension of the instrument’s perceived expressive range – is incalculable. His concertos are established in the repertoire, whereas the Totentanz (1849) is a neglected virtuoso masterpiece, exploiting the potential of the Dies Irae long before Rachmaninov. The much earlier Malediction is another powerful but rarely heard piece. D’Albert, one of Liszt’s pupils, wrote two piano concertos, No.2 in E major being a single-movement work. Liechtenstein-born Rheinberger is best-known for his many organ works. His Piano Concerto in A flat dates from 1877. Stavenhagen’s Piano Concerto in B minor shows the influence of his teacher Liszt, while the Concerto in D flat by the Norwegian Sinding (who wrote the celebrated Rustle of Spring) is one of the relatively few Scandinavian examples of the genre.

„Romantic Piano Concertos“ bei Briliant Classics: Leopold Kozeluch/ Wiki

In addition to the improvements in piano production another factor contributed to the development of the piano concerto, namely the expansion of the standard symphony orchestra. Trombones, percussion and other ‚heavier‘ instruments were integrated, and although many composers chose not to use them (in the interest of balance), they were available to contribute a wider range of tone-colours or extra weight.

Saint-Saens, who composed five concertos and shorter works for piano and orchestra such as the Africa Fantasy, was described by Liszt as the greatest organist in the world, and his mastery of the piano was obvious at a very early age. He did much to revive the classic forms such as the concerto and symphony in France, at a time when much lighter fare was fashionable. Of his concertos, which span 40 years, only No.2 is a repertoire piece, though Nos. 4 and 5 are occasionally performed. His First Concerto (1858) has a slow movement including little cadenzas of almost impressionistic writing which anticipate Ravel by about 50 years. The much more familiar Second Concerto begins with a long unaccompanied passage for the soloist and has an unusual structure of three progressively faster movements. The Fourth Concerto has a remarkable structural unity unparalleled in terms of the 19th-century concerto, while the Fifth Concerto has a slow movement including a curious modal passage and some impressionistic figuration which again anticipates Ravel. The extraordinary sonority of the modal passage (left hand mezzo forte, right hand pianissimo) must surely have been inspired by the bell-like sounds of Indonesian gamelan orchestras at the 1889 Paris Exhibition.

Saint-Saens‘ compatriot Lalo wrote only one piano concerto, while other French composers showed even less interest in the virtuoso romantic genre. In his engaging Piano Concerto Lalo retains elements of the grand manner but otherwise the solo writing is more notable for its degree of integration into the orchestral texture. Debussy’s early three-movement Fantaisie is decidedly in the Romantic tradition, while the spikier lyricism of Roussel’s Piano Concerto of 1927 shows an affinity with Prokofiev. Frangaix’s concerto is as piquant and witty as it is Romantic but is an entertaining work by another unjustifiably neglected composer. Tailleferre, the only female member of Les Six, wrote her attractive Ballade in 1920.

Tchaikovsky’s bravura piano-writing, especially in his famous and virtuosic First Concerto, shows Liszt’s influence. His Third Concerto is a rarely played single-movement work, while his Concert Fantasy is even more neglected. Of the other Russian Romantics Lyapunov, Balakirev, Glazunov and Medtner (a late-Romantic) all produced concertos and other compositions for piano and orchestra. Medtner’s music in particular – including three piano concertos – was very highly regarded by his contemporary Rachmaninov. Anton Rubinstein was one of the supreme virtuosos of the 19th century and a towering figure in Russian musical life who became composition teacher to Tchaikovsky. The fourth of his five piano concertos proved to be a great influence on Tchaikovsky’s own concertos. The Swiss-born composer Raff wrote a vast amount of solo piano music but just one Piano Concerto in C minor, in which his considerable lyrical gift is evident. His Ode to Spring is a poetic piece of programme music with a rather stormy middle section.

„Romantic Piano Concertos“ bei Briliant Classics: Mily Balakirev/ Wiki

Dvorak’s Piano Concerto is much less frequently performed than his concertos for cello and violin, but has been championed by some outstanding musicians. The Spaniard Albeniz wrote a

Concierto fantastico influenced by the earlier Romantics, while the Hungarian Dohnanyi, at one time the pre-eminent musical figure in his native country, wrote two concertos which have been overlooked in favour of his Variations on a Nursery Tune. Like Franck’s Symphonic Variations, this fine work used to be regularly played at the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts.

Paderewski’s Piano Concerto dates from 1888. Thirty-one years later he became Prime Minister of his native Poland, but his virtuoso performances brought him more lasting international popularity.

Busoni, a fascinating blend of Italian and German temperaments, was a formidable virtuoso in the Lisztian tradition who wrote an extended piano concerto with men’s chorus in its finale. His Konzertstuck is much shorter than the 75 minute concerto but nevertheless spacious and ambitious.

The London-born Litolff composed five works with the unusual title of Concerto symphonique. The scherzo from the fourth of these is a great favourite, but No.3 is a fascinating work, no less virtuosic in spite of its ’symphonic‘ qualification. Moskowski wrote many small-scale piano pieces including the popular Spanish Dances. Of his two piano concertos the early work in B minor was only rediscovered in 2011, while the engaging E major Concerto was very popular in the early 19th century and does not deserve its current neglect. Retaining the ‚grand manner‘, Reger’s turbulent Piano Concerto has a solo part demanding great stamina. The Polish/German Scharwenka composed four piano concertos, superbly written for the virtuoso performer and well deserving of revival. The Italians Respighi and Casella, the former the more unashamed Romantic of the two, both wrote large-scale concertos for the piano. Casella’s A notte alta is an atmospheric piece of meditational character.

Some of the late-Romantic composers were American – MacDowell, Gershwin, Daniel Gregory Mason, Amy Beach and Barber. MacDowell’s Second Concerto is replete with Romantic gestures, as is the Concerto in C sharp minor by Amy Beach, who is equally rooted in the Romantic tradition. Gershwin is a one-off, arguably the only composer ever to have successfully combined jazz and symphonic elements. His Piano Concerto is influenced by the Romantic tradition, Hollywood, the dance-hall and jazz, adding up to an infectious and memorable work well established in the repertoire. Daniel Gregory Mason is unknown to many, but his Prelude and Fugue is an impressive work. Barber was a strong representative of late-Romanticism, the abrasive elements of his Piano Concerto being outweighed by his characteristic lyricism.

With the 20th century came a new way of writing for the piano – more brittle and percussive. Bartok, Stravinsky and Prokofiev all employed this anti-Romantic manner, but many other composers continued the Romantic tradition which had flourished for well over a century. © Philip Borg-Wheeler

Foto oben: Franz Liszt Fantasizing at the Piano (1840), byDanhauser, commissioned by Conrad Graf. The imagined gathering shows seated Alfred de Musset orAlexandre Dumas, George Sand, Franz Liszt, Marie d’Agoult; standing Hector Berlioz or Victor Hugo,Niccolò Paganini, Gioachino Rossini; a bust ofBeethoven on the grand piano (a „Graf“), a portrait ofLord Byron on the wall, a statue of Joan of Arc on the far left/ Wiki