Bel Canto Bully, the life and times of the legendary opera impresario Domenico Barbaja is a surprising book in many ways. First of all, it was surprising to me that no biography of Barbaja existed before Eisenbeiss published his work. Barbaja was probably the most influential opera impresario of the nineteenth century, and no one who delves into the operas of the primo ottocento, especially works of Donizetti, Bellini and in particular Rossini, will get far before encountering his name. His importance in bringing the work of these and other composers to birth is hard to overestimate. Barbaja’s rise from a peasant farm background through work as a coffee house waiter to a wealthy impresario familiar with royalty and the principal singers and composers of the day is in itself an extremely surprising story, a sort of rough-hewn Cinderella tale in its own right.

Philip Eisenbeiss has been living in Hong Kong for the past 20 years, where he has been working as a banker and financial headhunter. After extended training as an opera singer, he started his career in journalism.(Haus Publishing)

Another surprise is that a work of such importance as this musical/business biography would be undertaken not by a professional musicologist or historian, but by a banker and “financial headhunter” who lives in Hong Kong, far from the venues of Barbaja’s triumphs in Italy and Austria. But then, perhaps Eisenbeiss’ background as a thwarted opera singer, a journalist, and a business man make a perfect background for writing about a figure who was, first and foremost, a business man and not a musician, although one whose business was music.

Maybe the reason that no one has previously undertaken a biography of Barbaja is the impossibility of obtaining primary source material from the man himself. Barbaja was born of itinerant farmers in a small town near Milan in 1777 (or 1775 or 1778–the exact date is open to question), and he left school at an early age to work in the popular coffee houses of Milan. He apparently never learned proper Italian and throughout his life conversed in the Milanese dialect, which like the Neapolitan of his adopted city, is almost a language unto itself. Thus Barbaja was uncomfortable with the written language and wrote as little as possible, leaving us guessing a lot about his ideas and beliefs. This is in contrast to Rossini (or Bellini, Donizetti or Pacini) who were copious letter writers, and whose surviving letters, documents and memoirs give us sufficient source material to create convincing portraits of them.

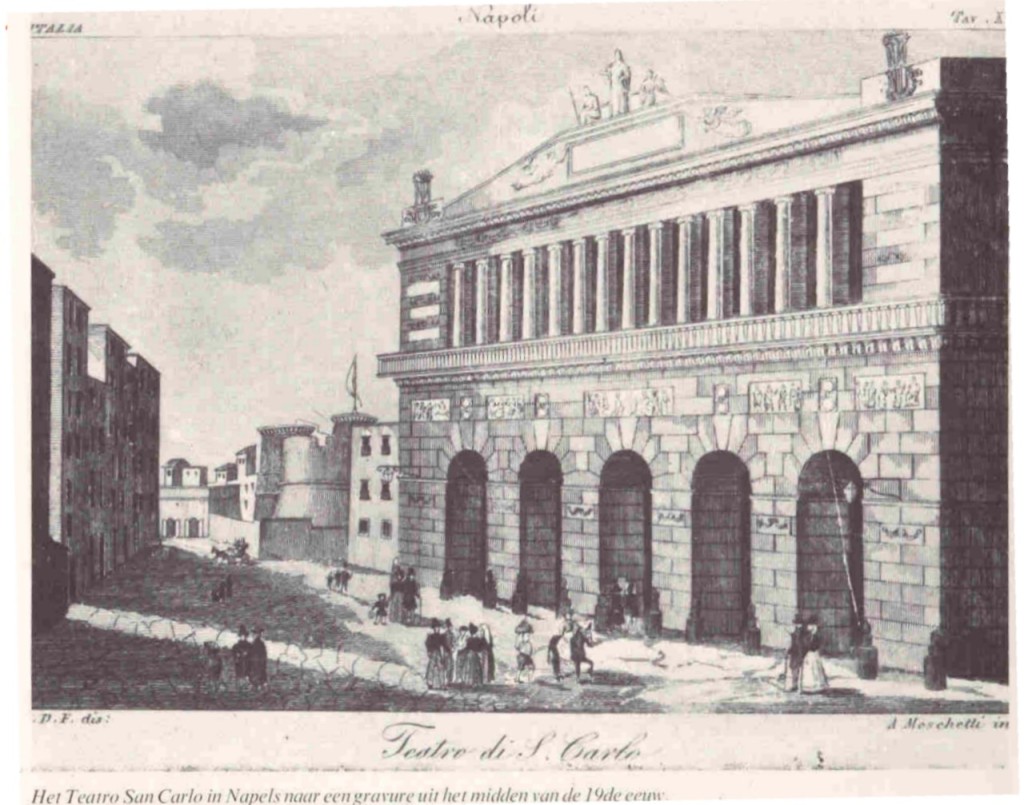

Most of what we know about Barbaja, however, comes from what others said about him, which was not always complimentary. As Eisenbeiss points out, Barbaja was a hard task master (although calling him a “bully” in the title may be going too far). As impresario of the Teatro San Carlo in Naples, Barbaja seemingly had an unerring ability to spot great talent in both composers and singers while it was still nascent, and to lock young artists into favorable contracts before they became famous. This ability allowed him to make Naples’ San Carlo the greatest opera house in Europe with the willing support of the Bourbon kings of Naples and with his own great wealth, much of it acquired from his cut of the gambling revenues taken from the gaming in the foyers of the theater. It also created enmity from singers and composers who, once famous, found themselves locked into contracts they had outgrown. And Barbaja loved litigation.

As a young man in Milan, two centuries before Starbucks, Barbaja had invented a coffee drink that combined chocolate, coffee and whipped cream and made him locally famous. (That drink, called a barbagliata, is today commemorated in a tasty gelato that one can purchase in the intervals of operas across the square from the Teatro Rossini in Pesaro.) From there he parlayed a small fortune made in arms dealing during the Napoleonic period into his work as an opera impresario and gambling executive. In short, Barbaja was a consummate business man, able to accumulate money, and lots of it, in whatever enterprise he chose.

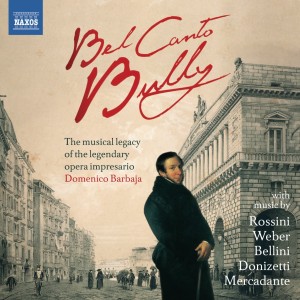

Naxos hat – apropos „Bel Canto Bully“ – eine Zusammenstellung mit Musik aus dem für Barbaja geschriebenen Repertoire herausgegeben

Being an opera impresario was a risky business in nineteenth century Italy, and many an impresario went bust trying bring order out of chaos, but not Barbaja. Eisenbeiss aptly compares him to a movie mogul of Hollywood in the 1920’s or 1930’s. Barbaja practically created the star system long before Samuel Goldwyn, and he had a “stable” of operatic stars that made “his” house, the San Carlo, the toast of Europe. But he was also canny in loaning out his stars to other houses and impresarios. He built an empire that eventually included the Kärntnetortheater in Vienna and La Scala in Milan. At his height, he was running three of the most important opera houses in Europe, and leasing his stars to Paris, London and other centers. And aside from the Italian composers whose work we associate with him, he also championed the work of Carl Maria von Weber, and was responsible for the premiere of that composer’s Euryanthe in Vienna in 1823.

Barbaja had a palazzo on the Via Toledo in Naples (still the principal street there) close to the San Carlo and the royal palace, where he housed many a composer and singer on contract to him–the free room and board was an inducement along with what could be a fairly meagre salary. There was another palatial house in the Mergellina District on the Bay of Naples and a summer house on the island of Ischia. He was such a man of substance that it was assumed in 1816, when the San Carlo burned to the ground, that Barbaja was worth more than the King. At any rate he promised the King to rebuild the opera house, and he did, in just nine months, an extraordinary feat. Barbaja acted as a general contractor for that architectural project and for another–the building of the Church of San Francesco di Paolo. Today, visitors to Naples who marvel at the wide expanse of the Piazza del Plebiscito and the Church of San Francesco which faces the Piazza, hard by the opera house and the royal palace, are unlikely to know that they should thank Barbaja. And opera-goers whose eyes widen on entering the ornate grandeur of the San Carlo for the first time, probably do not know that Barbaja was behind it all. At the time of its reconstruction, the San Carlo was not only the largest opera house in Europe, but the first with indoor plumbing and bathrooms!

Although he had a wife (and children) in Milan, whom he rarely saw, he probably had many mistresses in Naples, most famously the great singer Isabella Colbran, who left him to become Rossini’s first wife, and who starred in most of Rossini’s opera serias composed for Naples. This well known fact is a case in point in regard to the lack of primary source material for Barbaja’s biography. It would be fascinating to know what Barbaja thought of Colbran leaving him for his star composer, but no letter has survived, or was probably ever written. We know that Barbaja’s business relationship continued after the Rossinis’ marriage, but the relationship grew more contentious. We also know that the three of them spent many weeks together in Barbaja’s villa on Ischia before Colbran and Rossini became an ‘item’. But, frustratingly, we have no idea what Barbaja thought about it all. The person Barbaja remains something of a cypher.

If Eisenbeiss’ biography lacks something, it is this, and he cannot be faulted for it: too often we know what other people think about Barbaja, but not what he himself thought. About the business that Barbaja ran, however, Eisenbeiss can teach us a lot. Contracts survive, and records of law suits, and the like, and the few letters we have from him deal, in halting Italian, strewn with mistakes, with business matters. Many of us who have studiedprimo ottocento Italian opera as professionals or as an avocation will find many facts and anecdotes here that we have encountered before, say in a biography of Rossini. But few of us will have seen these facts and stories through the prism of a business relationship. Nor would many of us be aware of Barbaja’s contributions outside of his relationships with Rossini, Donizetti, et. al. I also found Eisenbeiss’ section on historical monetary values fascinating–how much Rossini would be paid for an opera in modern terms, or how much a star singer could make in a year in today’s terms. Like Hollywood movie stars, the opera stars of the early nineteenth century were paid a lot more than the composers of the music (like the script writers). Mr. Eisenbeiss places his study of the music business in a clear historical context, which sometimes assumes that the likely reader knows less about the era than he or she probably does. However, it is always helpful to have the confusing history of Naples in those years spelled out, or the international political context of Barbaja’s business dealings.

Finally, Mr. Eisenbeiss writes in a clear English prose which is never dull or overly academic. He treads a middle road between the well-grounded (and footnoted) work of the professional historian and the work of a popular writer. What could be a dull compendium of historical fact is anything but. Barbaja was an incredibly dynamic figure and a fascinating one who embodied a myth that Americans have always loved, albeit in an Italian context: a street smart, rough-hewn boy who begins with nothing and ends up rubbing elbows with kings and princes, not to mention the most culturally significant figures of his time.

At the end of his book, Mr. Eisenbeiss has an appendix of “the Barbaja Operas,” the 70-odd works for which Barbaja was the impresario, the man who had them staged for the first time anywhere. There are three works by Bellini, twenty-eight by Donizetti and ten by Rossini, among many others by less well known composers. When we go to see La donna del lago in London or Santa Fe or Pesaro this summer, or when we seeRicciardo e Zoraide at Bad Wildbad, we have to thank Domenico Barbaja, impresario extraordinaire, and we should be grateful to Philip Eisenbeiss for reminding us of his importance and his part in the birthing of so many masterpieces.

Charles Jernigan

Den Artikel von Charles Jernigan, operalounge.de-Lesern kein Unbekannter mehr, entnahmen wir dem hochinteressanten Blog des Autors mit Dank: Jernigan´s Journal

Bel Canto Bully, The Life and Times of the Legendary Opera Impresario Domenico Barbaja by Philip Eisenbeiss; Haus Publishing, 2013; ISBN: 978-1-908323-25-5